Mallika Sarabhai is one of India’s leading choreographers and dancers, in constant demand as a soloist and with her own dance company, Darpana, creating and performing both classical and contemporary works. She is a powerhouse of communication in India. Educated in business, she now leads the Darpana Academy of Performing Arts. She has been awarded by the Indian government with the Padma Bhushan, the third highest civilian award, in 2010. She’s also a writer, publisher, actor, producer, anchorwoman and all her varied forms of artistic engagements are wrapped around a deep social conscience.

Mallika please describe yourself in one word and then, in one sentence. You are a powerful communicator. One who uses dance, writing, choreographing, acting as your mediums to communicate. How did you become so versatile, where did it all start from?

One word: Humanist.

One sentence: Optimist who thinks the world can be made more compassionate.

It started with the way I grew up. My mother, as one of the first dancers with deep roots in classicism, was part of the whole excitement of India becoming independent and nation building, inspired by the Nehruvian vision of a different India. She thought that she could use her classicism to talk about issues that she felt concerned about then. I remember, as early as 1963, when she, who is half Tamil and half Malayali, married into Gujarat and started learning Gujarati by her teacher making her read the Gujarati newspaper, she came across what we now know as “Dowry Deaths”. She read these stories about young girls in Kathiyavad, soon after their weddings, jumping into the well and committing suicide. She was horrified by the whole phenomenon of the married family being so awful that these young brides committed suicide. And she created a piece in Bharatanatyam, which for me is the seminal piece of the journey that dancers took subsequently, because she used a language of classicism which only spoke of love and “shringara” and beauty, and used it for the first time to talk about dowry deaths and violence against women. Growing up in this household and seeing this work, I thought all dancers did this. I had no idea that Amma was so special in using dance to talk about this. So I grew up assuming that the arts were a language to talk about things that mattered to you. But it was not till I actually went to work with Peter Brook in The Mahabharata and saw the effect of my interpretation of ‘Draupadi‘ on audiences across the five continents, that I realized that I had been an artist and an activist, but that the best language for my activism was my art. So it was only when I came out five years later in the 1990, that this particular journey started of becoming what one would call an “Artivist”, this is not my word – it’s coined by somebody else. So that journey started in the five years that I was with The Mahabharata. I had always known that it was a fantastic medium, I just didn’t think that I could do it. As for writing, choreographing, etc, I was in some sense forced to do it because nobody could write the script which was in my head. I was forced to become a scriptwriter and a choreographer and a director and lyrics writer and, and, and…because I was so frustrated that nobody could understand what I wanted said, so willy nilly it pushed me into becoming a creator of thoughts.

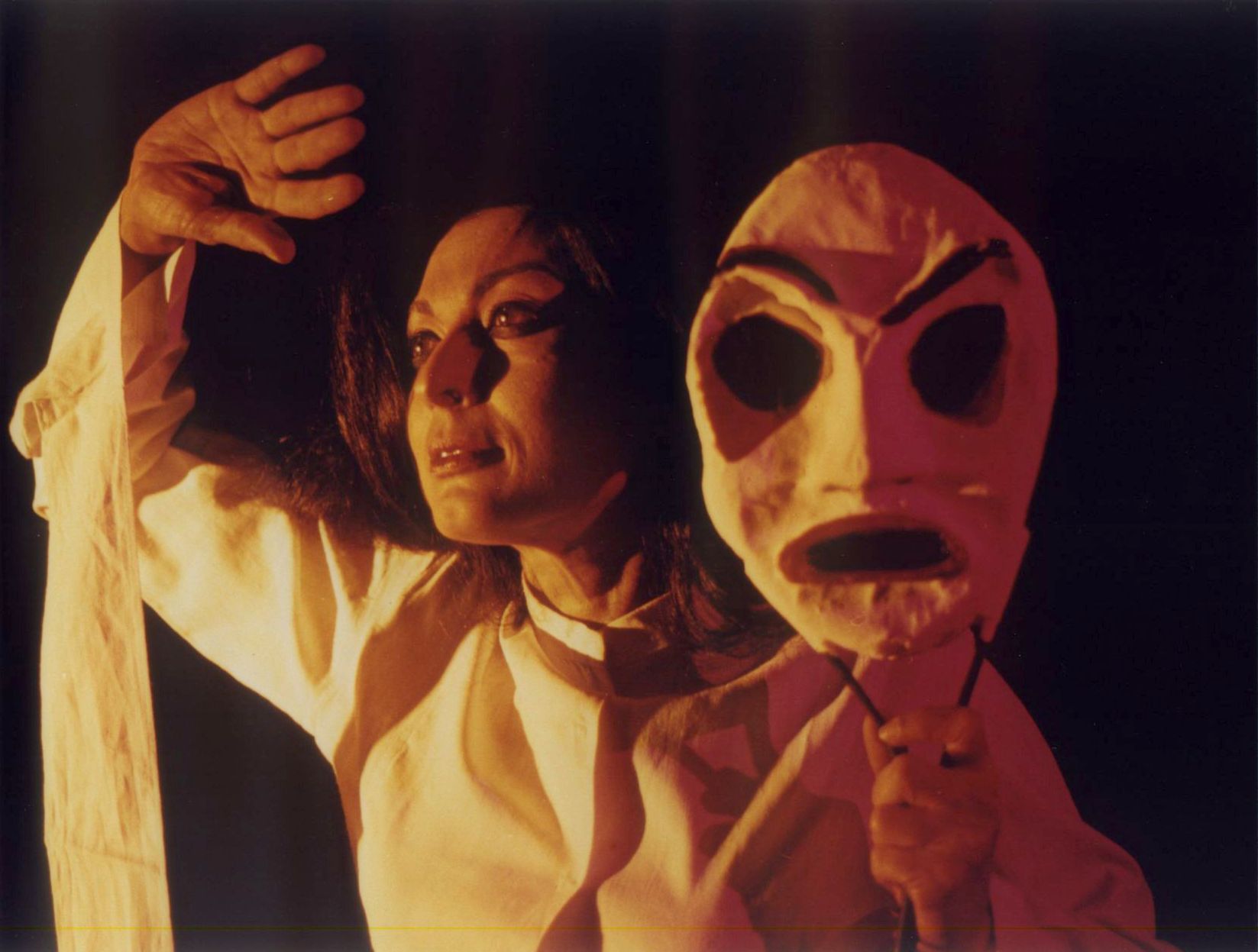

Playing Draupadi in The Mahabharata

Tell us more about the reactions people had when they saw the Mahabharata and the depiction of Draupadi?

Well, there was the reaction of the Indians and then there was the reaction of everybody else. But the first reactions were in the production of the play itself, because though Peter Brook, the director, and Jean Claude Carriere, the writer of the script, had both been studying the Mahabharata for eleven years, they are both white Anglo-Saxon men. For whom the idea of “Shakti” seemed to be alien in spite of all they had studied about it. So my early arguments were when they would say to me, “Don’t raise your voice you sound like a shrew!”, and I would say to them that we don’t have shrews in India we only have ‘Shaktis’. And if you don’t understand that then choose a less dramatic play, choose a less dramatic story. And I used to have these endless arguments with them. And it was only in the months and months of previews that we did, and seeing the way French audiences (because we started in France) were reacting to the character of ‘Draupadi‘ that they realized the power of the kind of woman that ‘Draupadi‘ was. So that was the initial whole break through. Then to my great disappointment, but not to my surprise, 99% of Indians, who saw the play, had one question which is – “why do you have black people playing our characters?” Nobody was non-racist enough or pro-Indian enough to say to me “why do you have foreigners play us?”. That I can understand, that is a point of view. But nobody said “why is ‘Yudhishthira‘ blond and blue-eyed, they only had an objection to Blacks playing anything. By the end of it this was the only question. We were thinking of not bringing the play, but bringing the film and television series to India, and travelling with a group of artists, three of whom were extraordinary Black artists – one who played ‘Bhima‘ and one who played ‘Bhishma‘ and one Moroccan who played ‘Krishna‘. I had in fact warned them that we are an extremely racist country and this is going to come up and sure enough at every workshop it came up. And by end of the tour in Bangalore I was so fed up that when one gentleman from the audience got up and said “why do you have Blacks playing our Gods?”, all I could do was pull out a mirror from my handbag and show him that he was like six shades darker than any of the Blacks on stage. So those were the reactions. But I had women from very very sort of chic young students from the Sorbonne, to aboriginal women in Perth and Adelaide, to big black mammas from the Bronx coming to me and basically saying that “this is the women we identify with, why don’t we have more role models like her coming out of India?” That’s when I realized that, my God, just one character in this play and if this is the reaction I am getting then obviously I am using the wrong languages for my activism, and what I have in my hands, as a fields of arts, is the most powerful language I have.

You have been a strong advocate for women’s empowerment. Tell us about the use of art to bring about social change. Most people view art as a form of entertainment and hobby, how can we use it in the same way like we use STEM fields to bring about a change?

Many different reasons, I would say the most important reason is that we, and I mean “we” the world and not “we” India alone, are ruled by what goes on in the United States. The United States being a young country did not have two-thousand years of history, which Europe had, which Japan, China or India had, in using the arts to talk about ‘Good’ and ‘Bad’. If you go into Greek mythology, if you go into churches, what are those paintings? They are the use of art to show what is good and what is bad. If you go into Indian temples, if you listen to songs, everything was about education. It was a different kind of education but it was still about education. It was not about pushing your navel up and down.

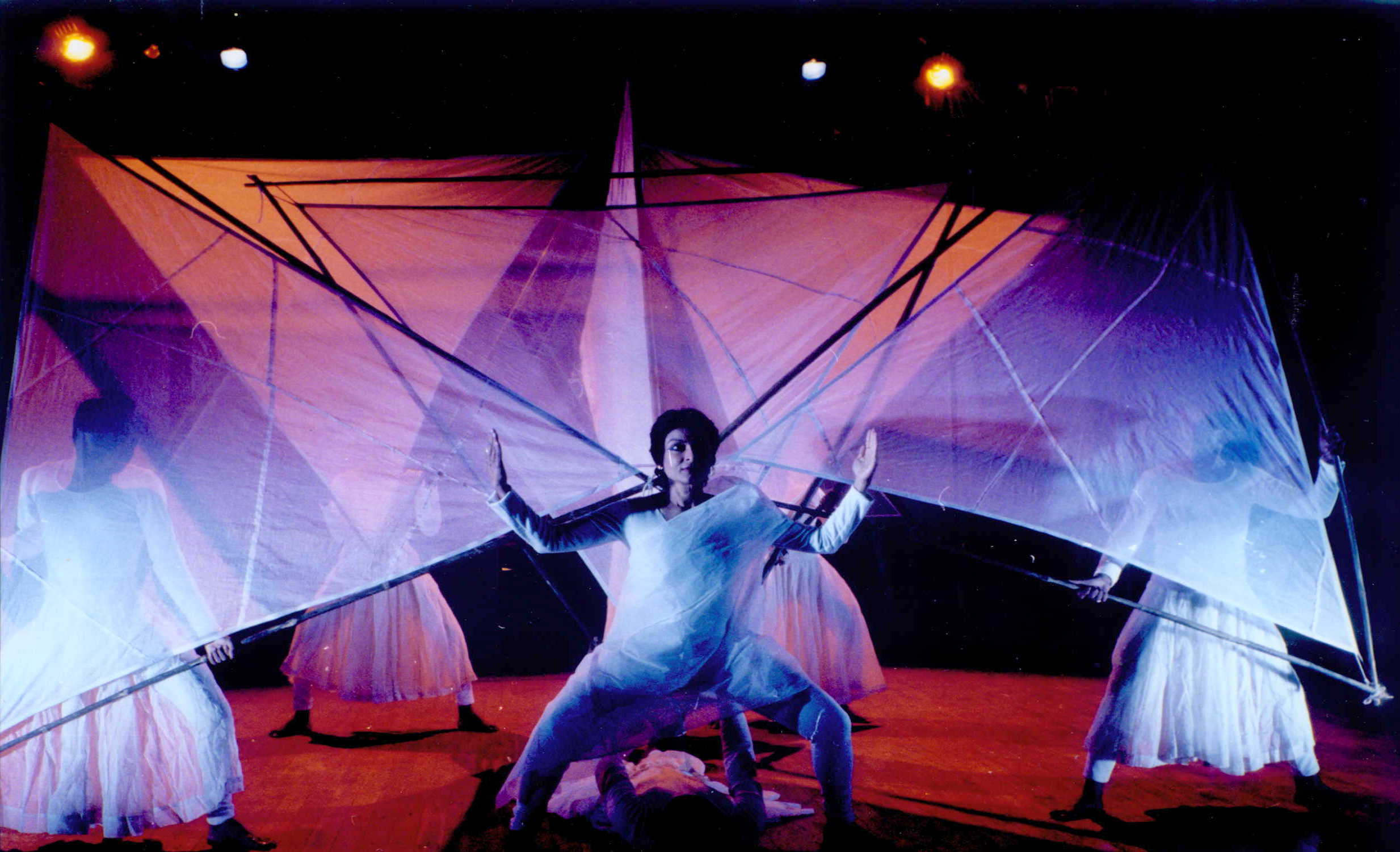

Contemporary

Contemporary

All the ancient traditions, if you look at storytelling, if you look at traveling drama, Punch and Judy show in England! The Punch and Judy show was a critique of the political strategy and the political people of the time. Punch and Judy would get away with saying anything about the King or the Mayor or the Barren or the Noble, who ever was ruling because they could say. The ‘Bhavai‘ in Gujarat or the ‘Jatra‘ in Bengal or the ‘Tamasha‘ in Maharashtra played exactly the same role and they could get away. So the artists would come into the village early in the morning, they would listen to the gossip, they would hear about how somebody was corrupt and how somebody was having an affair with somebody’s wife, and how somebody was taking away money and not being fair and so on and so forth. They would weave all this into the play. So it was education, it was political education, it was religious education, it was ethical education. But it’s only in the last 125-150 years that we got stuck of it being entertainment. And I think a huge fillip to this was given during the first World War, when troops had to be entertained. They had to be titillated. They were away from women. They needed sex and they needed to be able to whistle at things, they needed to be able to basically get aroused by things because they missed home so much and they missed their women so much. And I think that had a huge impact on the way we perceived of the arts as being a part of the society. From being the yeast of the cake it became the cherry on top of the cake. And that is where the slip happened. Also the fact that when the British were ruling India, the Victorian age was on, and from the eyes of the Victorians, all Indian classical dance was considered unethical and tawdry. So they banned the ‘Devadasis‘, they banned dancing, and everything went underground. So there were several reasons but I think I have named the three that I think are the most plausible.

Talk about the challenges you have faced in conveying your message through dance or other forms of art. How did you overcome those challenges?

You know, I use a lot of mythology and reinterpreting mythology. And the first piece I did was in 1989-90, just after The Mahabharata, it was called ‘Shakti-The Power of Women’ and it reinterpreted Draupadi and Savitri. And I used to have a lot of right-wing Hindu backlash, and when I did my next piece which was called ‘Sita’s Daughters’, and I reinterpreted the Ramayana story from Sita who is about to go back into her mother’s womb and she looks at the Ramayana, and she questions the Ramayana. I used to have fairly vociferous and bordering on wanting to shut us down reactions from the right-wing that is now ruling the country. So there have been been some challenges but I have to also say that, for instance, when I was doing ‘Shakti-the Power of Women’, I have still the letter written by the head priest of all the Hindu temples and Hindu associations in Great Britain, and he said “Miss Sarabhai you have taken Hinduism back to the pristine glory of the Vedas.” So it was both ways.

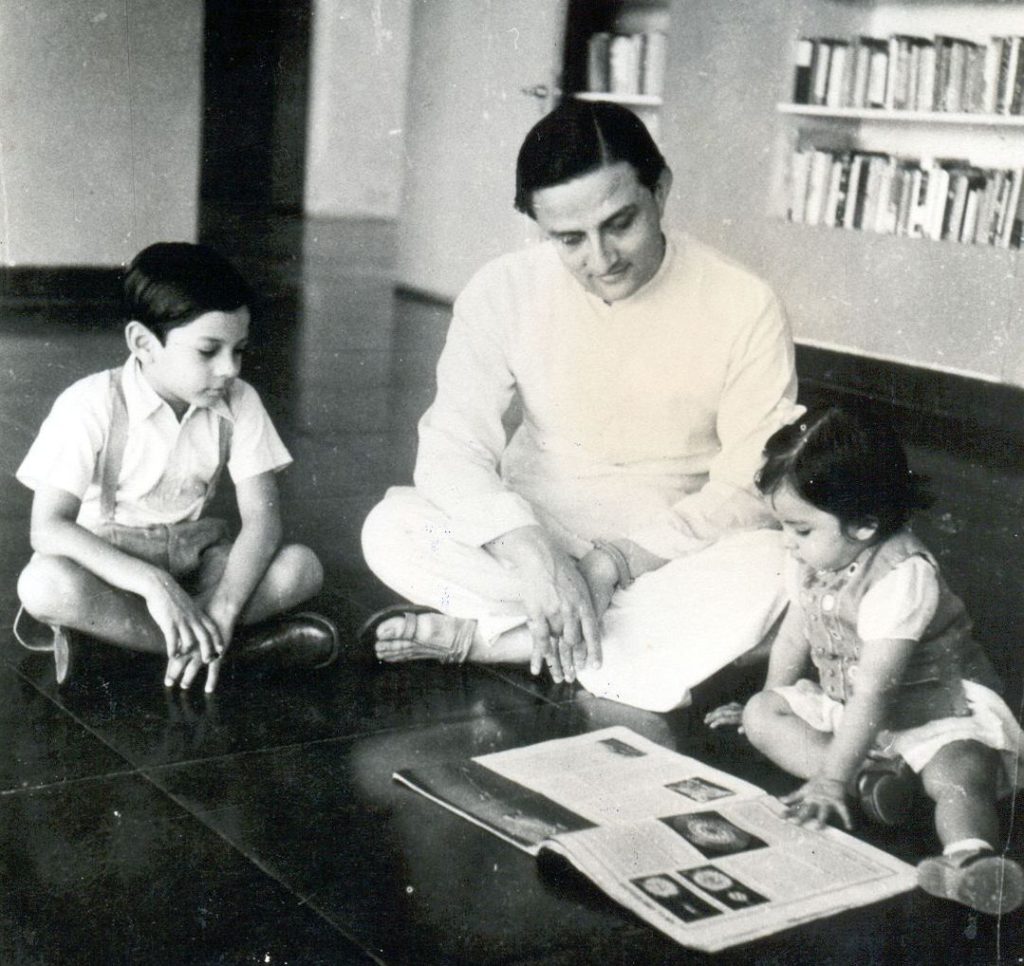

Your mother, Mrinalini Sarabhai, is an award-winning celebrated classical Indian dancer/choreographer and dons many different hats. Your father, Vikram Sarabhai, is considered the father of India’s space program. What was it like growing up with well-known/accomplished parents? How did they influence you? Is there a childhood memory that sticks out?

My parents were quite extraordinary in the fact that never once did they make me or my brother feel pressured that we had to achieve what they had achieved. For us, they were very normal parents. Because they were so happy in what they were doing, they never felt the need to sublimate what they couldn’t do through their children, which is what happens in most cases. So a mother who has never been able to learn how to dance will force her daughter to go to a dance class, whether she wants to or not. A father who wanted to be a doctor will force the child, and so on and so forth.

Mallika with Amma

There was none of that. There was always this feeling that whatever they accomplished was as a gesture of love to the family. We felt very strongly that we mattered more than anything else. And that was an amazing note to build self confidence and to feel self actualized.

But I remember, when we were very young, Amma used to tour a lot, and Pappa would stay home looking after us. They had made a pact that till I was twelve, one of them will always be here. My brother was older than me. I remember my first day in primary school. I was in this Montessori school and we were all asked to draw a face and I drew the ears in the wrong place. There was this little boy sitting next to me, who subsequently became a great friend, but that day he said to me, “You are an absolute ass, you don’t even know where the ears are.”

I got really upset. I came home crying, went to Pappa and told him that there’s a boy who calls me an ass and I’m not an ass. I refuse to go to that school. So Pappa said, “Mallika, what are you?” So I said, “I am a little girl.” So Pappa said, “Mallika, if he doesn’t know the difference between a girl and a donkey, then you should feel sorry for him. Why are you feeling bad?”

In many ways that must have imprinted itself on me. Because ever since then, whenever I have had extremely unfair things said about me, and there have been plenty, I’d remind myself of that. Especially when I took on the Government after the genocide in 2002, I was called names that you would not believe. I used to always say that’s their issue not mine. So if somebody calls me what they think is a dirty name, it’s their issue. I will only feel humiliated if I allow myself to be humiliated. Otherwise, someone insulting me is not an insult. How is it? This was a very important seed. It’s not that I don’t get insulted. But I have an ability to reason this through myself. I think to myself, why is your ego so fragile? That is one of the key elements in giving me the courage to walk my path.

You were a rebel and never conformed to traditional societal norms. Did you ever second guess yourself? What are some of the stereotypes and or prejudices you experienced?

I came from such a crazy family that on either sides, there was nobody who would conform to norms. I had an aunt who led the Indian National Army (INA) as the Commander-in-chief. She led the Rani of Jhansi Regiment from Singapore to India. I had another aunt who dressed as a Pathan to help women from Pakistan and India rejoin their families. I had a great grandmother who stood alone when the Mappila riots happened, in the 19th century and the early 20th century, and said to the marauding Mappilas, who were fighting against feudal exploitation of their workers, “I am a woman, I run this household and I run this farm. You can talk to my workers and see if they’re exploited. If they are, you can cut off my nose and do whatever you want but talk to them.”

So you know, they were all maverick women. I have had four generations of feminists, both men and women, and everybody marrying everybody. We had Greek orthodox sons-in-law and brothers-in-law and Buddhists and Jews and everything. It was considered this hatke family in many ways. People would say, “Oh the Sarabhais, they can do anything. Oh the Swaminathans, they can do anything.”

So, you know, had I been anything else, I’d have freaked my family out. My mother was the straight-laced one at that stage. For instance, when I started living with people. I would say to her, “Don’t you think I should get to know them before I commit to them? What if I don’t like them?” Then many years later when I walked into her office, she was telling this dancer who had come to tell her that she was getting married, “Why do you want to get married? Just live with him and figure it out.”

Mallika with her kids Anahita and Revanta

Yes, I was a rebel in the sense that when I was 16, I joined the film industry. And when I was 18, I had started smoking. So there used to be headlines in Gujarati newspapers saying, “She doesn’t even have the maryada, she isn’t even ashamed to show that she smokes in public.” Meaning it was okay to be hypocritical but it wasn’t okay to be open and I thought, what kind of a stupid society is this; I am not going to follow this.

You started dancing and acting at a very young age. Was it love at first sight always? What kept your going? You also went on to get an MBA from IIM-Ahmedabad and a PhD in Organizational Behavior from Gujarat University. Why the advanced degrees?

No, absolutely wrong. Till I was 22, the only thing I knew was that I did not and could not become a dancer because it was too much work and I did not have the stamina for it. I did not want to put in so much physical work. I always danced, I loved dancing, I loved being on stage, but I did not want to become a dancer. I wanted to become an actress, a demographer, and all sorts of other things.

In college, everybody wanted me to dance. I’d dance in college functions and win all the competitions. All my best friends would come to the class and dance. So I just felt peer pressure. But I was aware of all the hardships that Amma was going through. She had 105 degrees temperature and she had to dance. So I didn’t see the glamour of it.

What changed it was a bad love affair. I had just broken off my engagement with a man who turned out to be a male chauvinist pig. I went through severe depression, and one morning I got up and thought, “Oh God. What am I doing? All I want to do is get up and dance.” That was a moment of absolute epiphany for me.

I love studying. I am still an inveterate student. I am learning Malyalam, I am learning how to play the Dholak. I am forever learning. I love the process of learning. The sheer joy of learning, of speaking a new language, or learning how to draw, of learning pottery, whatever.

You are very passionate about women’s issues. You have enacted and written strong plays depicting women. What fuels that passion?

It’s the fact that there is a beautiful alternative out there. Only if women could switch off the switch in their heads, which somewhere deep down tells them that they need to be apologetic about being women, would we have an amazingly empowered, compassionate, and much kinder a world.

If women wear the boots of the family and try to become masculine, they’re doing it out of fear and out of a lack of self worth. Nothing can be stronger, gentler, and more cooperative than a woman who learns how to be feminine and a woman. That is why ‘Draupadi‘ is such a favourite. She says, “I have brains and a womb and I use both.” At one stage, she says to ‘Yudhisthira‘, “I love you very much but you’re a weak man who lies, and that is what is going to cause the destruction of this family. But that has got nothing to do with my love for you.”

How many women have the courage to do that? How many women have the courage to be strong women and not strong male clones? We measure ourselves up to men and that is our defeat. If you want to be like somebody else, you’re admitting that you are second class.

In Gujarati, a lot of parents of daughters say, “She’s not my daughter, she’s my son”, implying that she is so strong that she is a son. But sons are the weaklings. The daughters invariably are the strong ones. They are more educated, more supportive, more caring of older parents, and are putting up with a lot of tough circumstances. You know, it’s we who have to change that. And for me, that is a very exciting possibility. If out of a thousand people in the audience, I can actually change the trajectory of two, then that two is going to multiply into twenty two very soon. It’s like throwing pebbles and each one starts creating ripples.

Contemporary

There’s nothing more satisfying than being able to be the catalyst for a flower to blossom. That’s what keeps me going. Not that I don’t get fed up, disheartened or emotionally tired. All of that is true. But something happens that completely changes things.

I was coming back from Kerala three days ago. I was at the Mumbai airport for four hours. A woman, in her mid thirties, walked past me and smiled at me. She walked back, came and knelt down on the floor next to me, held my hand and asked, “Can I disturb you?” I said, “Yes, sure!”

She said, “You know, I was eight years old when I saw you perform in this village in Madhya Pradesh called Mandsaur. I remember every frame of it. I remember what you wore, what jewelry you had. You inspired me so much that I did twelve years of classical dancing. I then went to the National School of Drama, completed my course. Now, I teach theatre at a school in Nashik. I just wanted to tell you that there is not a minute when I shut my eyes and I don’t see you.”

Where does something like that come from? I feel so, so humbled. In the middle of Mumbai airport, with ten thousand people around, completely unexpected and unasked for, I meet this person. It makes you feel deeply moved.

What are some of the disciplines required to become a professional dancer? What advice would you give to aspiring dancers/choreographers looking to taking up dance as a profession?

It’s hard, physically and financially. You have to be true to yourself because it is very easy to get lazy once you get famous. I know a lot of very lazy, fat dancers who are very famous. You need to be more and more disciplined as you go on, especially in India where we don’t retire everybody at forty. Dancers bring in more of their experience and their Rasa in their dance, and musicians bring in more of their life experiences into their music.

Mallika doing classical dance

I still do Yoga for an hour every morning and rehearse for four hours every day. If I can’t rehearse, I walk eight or ten kilometers. I am still very careful about what I eat. I see that I meditate every day. I see to it that I do everything that makes my body feel good. My body is my machine, my temple, my everything. I spend time saying thank you to my body every day, because that’s what’s allowing me to dance. It’s very, very hard. I’m not talking of being a film star. I am talking of being a serious artist. Whether it is theatre or dance or music, there’s no scope for laziness. For every day that you don’t do your bit, the next day becomes harder and then you slip. It’s very easy to slip and injure yourself. I’ve always wanted to learn how to ski, but I have never, ever dared because if I break an ankle or a knee or something, what will happen to my dancing? So, you have to give up on things. You have to be strict with yourself in the regimes you follow. You have to love every rehearsal more than you love a performance. More than you love the adulation; you need to love the work out. Before a show, you’ll have to rehearse for a thousand hours. And if you’re taking shortcuts because you don’t enjoy that, then you’ll never be the artist that you should be.

Tell us about the shift you are seeing (if any) in India related to violence against women? Why have things not worked in the past, what needs to be done differently?

The levels of misogyny that we see today that are actually just under the surface, but are now coming to the surface is frightening. I don’t feel that women have been more abused in this country as they’re being right now, than in any other decade or century. You’ve a huge increase in gang rapes and acid attacks. You have a huge increase in gang rape cum hanging, gang rape cum burning, gang rape cum murder, and I think I have never felt more despondent. I think my next five years and the next five years of Darpana as an institution are going to be committed to working with men. Because it’s only the men who can stop the violence against women. The good men who have been silent have to get up and shout from the rooftops. We need to work with very young boys to make them understand that being macho is cowardly, it’s not bravery, that they can be in touch with their emotions. Unless we work with children, who grow in this process of socializing that gives them ideas like ‘boys don’t cry’ – it starts at the age of one, and unless we work with boys and men and parents of boys and men, we are not going to see a change.

The kind of sweep we need to see is a ten year gender sensitization plan that goes from the top, i.e. the Prime Minister and President down to the last rural worker sitting in some village. Unless there is that kind of, I hate to use the word – war footing, just saying Beti Bachao will do nothing. It’s nonsensical.

We need a change and commitment that I do not see in any government or any faith leader or anybody in this country. Unless we have that, nothing is going to change. Things will only become underground. We have never seen so many states taking up the Khap route and murdering people. The Khaps have now spread from Haryana, Rajasthan to parts of Gujarat and the states of the south where there are now Khap deaths. We’re in a worse position today than we’ve ever been. Women are more at risk today at every level than they have ever been.

What is Darpana doing in the direction of gender sensitization?

We have a project by the name of STAGE: Sensitizing Through the Arts for Gender Equality. We want to work in twenty colleges over a three year period, sustained work in trying to make a brigade of young people who understand that everything from the language they use, to the rituals they use, to the ceremony done at a wedding, all have an inherent violence against women. And unless we understand it, we are not going to be able to delink it to make a gender safe society.

We want to work on a sustained basis in the same colleges, because with a patriarchal bias that we’ve had for five thousand years, a one shot thing cannot change attitudes. It can change the immediate behavior, but it cannot change the mindsets. The only thing that’ll create a change is a huge shift in mindsets. Knee jerk reactions are all that we’re getting, which are completely hopeless.

What is your idea of an empowered woman?

An empowered woman to me is somebody who doesn’t identify herself as a woman first, but is empowered so that she can think about other things and can say I am a human being, I am an individual. To me that can only happen if I am so comfortable with being a woman that I don’t need to think about it, just as I don’t need to think about breathing.

Sayfty’s mission is to Educate, Equip and Empower women so that they can protect themselves against violence. What is your message for our readers related to women’s personal safety and the issue of violence against women?

The only advice I’d give is the advice I give myself. You need to go deeply inwards before you go outwards for empowerment. You need to analyze yourself; the words you use, the thoughts that come into your mind, the kind of comments you make. You need to make yourself bias free. Even eight layers down, I have some biases and I need to work on those and try and understand them. I need to understand my own inadequacies that are built by society and patriarchy. Only then will I be able to free myself. I tell women that you are mothers or you will be mothers. By bringing up your children to be humane beings, you will change the society.

Bio

Mallika Sarabhai is one of India’s leading choreographers and dancers, in constant demand as a soloist and with her own dance company, Darpana, creating and performing both classical and contemporary works. She has been the director of the prestigious arts institution, Darpana Academy of Performing Arts, for nearly 35 years.

She first came to international notice when she played the role of ‘Draupadi‘ in Peter Brook’s The Mahabharata for 5 years, first in French and then English, performing in France, North America, Australia, Japan and Scotland.

Always an activist for societal education and women’s empowerment, Mallika began using her work for change. In 1989 she created the first of her hard-hitting solo theatrical works, Shakti: The Power of Women. Since then Mallika has created numerous stage productions which have raised awareness, highlighted crucial issues and advocated change, several of which productions have toured internationally as well as throughout India.

In the mid 90s Mallika began to develop her own contemporary dance vocabulary and went on to create short and full-length works which have been presented in North America, Scotland, Singapore, China and Australia, as well as in India.”

Education

MBA, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, India, 1974.

PhD in Organisational Behaviour, Gujarat University, Ahmedabad, India, 1976.

BA (Hons), Economics, St. Xavier’s College, Ahmedabad, India, 1972.