Shilo Shiv Suleman is an Indian animator, illustrator and visual artist based in the city of Bangalore. Her primary area of interest is visual storytelling through multiple mediums. Shilo’s practice focuses on the intersection of magical realism, art for social change and technology. She illustrated her first book for children at the age of 16 and has illustrated eight others since with some of the most well known publishing houses in India. She is the founder and director of “The Fearless Collective” that engages with gender issues and art for social change in India. She has been actively involved in setting up community art projects and collectives that get people to appreciate and create street art in their surroundings as well as use art and design to bring socially relevant issues in India to the forefront.

Shilo Shiv Suleman – visual artist, digital storyteller, animator, stage designer, App designer, speaker and agent of social change. You wear many hats! How did it all begin? When did you know you wanted to become an artist? Tell us a bit about your early life.

My mother’s an artist as well. She is a single mother and pretty much brought up me and my brother on her own. Very early on, at the age of eleven or twelve, seeing her, I felt two things: One, as long as you do what you love, things work out. And two, that women are strong, capable, amazing and independent people. Just entirely doing things that she loved, she was able to bring up two children. For me, that was something that was already very deeply set in.

Shilo with her mother Nilofer Suleman

I started painting when I was around eleven or twelve years old. Back then, I used to paint huge canvases. When people would ask me what I did, I wouldn’t tell them that I was in the sixth grade or in the eighth grade. I’d just tell them that I am an artist! And I think that very deep sense of confidence came from my mum. So I started painting primarily as catharsis, as a way of dealing with my parent’s separating, but eventually it became a really beautiful connection, it just became my life essentially. It came out of places of fear, but it became everything that we love.

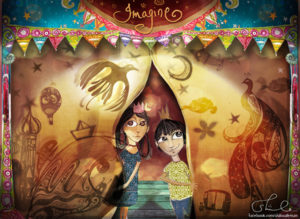

By the time I was sixteen, I was illustrating books for children. I was rediscovering the child in me. As I was growing up, I realized that I wanted to hold on to the magical worlds that I inhabited as a child. And actually, a lot of my background as a children’s book illustrator also very much reflects the work that I do right now, even with the Fearless Campaign. I illustrated children’s books for many years. From there, I started to get really interested in technology and seeing how I could use technology to enable magical, wonderful, wondrous experiences for people. I was particularly really interested in magical realism and enabling people to see wonder in everyday experiences and in the technology that we use in the rituals that we create around ourselves.

Illustration for a children’s book

What does magical wonder mean? What’s the idea behind it?

Well, I think as children, we use magical realism as a platform for empathy in some sense. So, I do a lot of work with storytelling in particular. And when we tell stories especially as children, essentially what’s happening is that by listening to the story of the bear and the forest, or of Rapunzel, or of Durga, we’re essentially becoming closer to all of those people. We’re seeing ourselves inside all of those people. So I think a lot of magical realism and storytelling that we had as children, if we apply it in our everyday lives, it enables us to be a little bit more empathetic, hopeful, and to be more trusting of ourselves. That’s the current thought experiment.

Apart from your mother who was a big influence in your life, who else played a role in influencing you or encouraging you?

Well actually it’s interesting because every time this question comes up, I think of this really beautiful Maya Angelou quote, where she talks about how when she walks into a room, the reason why she feels so confident is because it’s not just her, it’s not just one person, but she’s walking in with two thousand other people. She’s taking the story of Heidi in the mountains, she’s taking every story that she has ever read, she’s taking all of the ancestors she has, and she’s taking every influence of her with her into the room. So for me too, in terms of the influences I carry, it’s a whole range of women and men, sometimes mythological, sometimes cultural, sometimes personal. So starting with all of the interesting figures in mythological tales, both in Sufism and Hindu mythology, there are so many inspiring figures. So definitely a lot of them are a part of my larger landscape of influence.

In terms of cultural icons and figures, I think I am surrounded by them. For example, the story of Akka Mahadevi who is a 14th century poet from Karnataka. She took off all her clothes and went running through the forests, writing mystic poetry. And all of her poetry is about the female body, and the gaze. She is an influence as well. So basically there’s a whole range of influences: mythical, real, folk. But in terms of real people, it would definitely be my mum, and also the whole community of almost sisters that I’ve made over the years. So, friends who I feel like I have very deep connections with, and with all of the work I do, and Fearless in particular. Whenever I talk of Fearless, I talk in plural terms. I always say ‘We’ the Fearless, we’re doing this. Because I feel that it’s a range of different influences, opinions that add up. So I think I am those two thousand people when I walk into a room.

Why did you pick painting or illustration as a medium of storytelling?

I don’t think I’ve picked my medium. I know that I am a storyteller, that’s for sure. But apart from that, I haven’t. Because I started off as an illustrator, but now the things that I am doing are not necessarily related to illustration. Now, I am doing large scale installations in the desert, or I am doing stages. Even though visual storytelling is the base of it, I feel like I am still evolving, which is amazing.

Pulse & Bloom – an honorarium grant from Burning Man for the interactive project

Do you have a style that you can call your signature style? Or are you always trying out new things?

No. The style is the same. It’s evolving for sure, but at the same time, if you spend enough time in my house, you’ll realize that there’s no separation between me, my house, what I wear. Everything, eventually is my art. I feel like I am living my art in every aspect of my life.

Also, in terms of core concepts or philosophies that have stayed close to me, I’ve always been very consistent. I am not minimalist. I am incredibly abundant. It’s just that the way my abundance takes form has changed over the years. I have great belief that beauty can transform us. And I don’t mean beauty in the way that is sold to us on big billboards. But it actually ties back to wonder and magical realism as well. I feel that there’s a beauty in experience, and a beauty in form, especially in the natural world, that can transform us. There are some things that are very specific to my work, some ideas and core philosophies that are very specific to my work, but the work itself keeps evolving as I evolve.

Where do you look out for inspiration? How do you come up with new ideas and know that this is a new project that I need to take up?

I feel that my whole life has become a big canvas at the moment. There’s no real sense of separation. There’s no where something ends, something else begins. Sources of inspiration range from old lovers to patterns on trees to the way that the flower opens to the way the wind feels on my skin to stories, mythological stories to all of it. Everything is both feeding itself, as well as creating itself. I think that’s what nature actually does, right? It feeds itself and it also creates, generates itself. So I feel that my artistic process mimics the natural, creative process in that sense.

Is there an artwork/project that’s your favorite? You’ve done so many now. Is there something that’s really close to your heart?

It depends. If you asked me this question two years ago, I’d have said the stuff that I was doing back then. The things that I am working on right now are part of my larger thought experiment and heart experiment. I am always in love with what I am doing right now. Right now, I am working on a larger body of work called ‘Beloved’. It is more of my own personal practice. It’s almost like a split personality, but a more positive split personality. Because, on one hand, there’s Beloved, which is very intimate and very much like my own personal explorations, and then on the other hand I have Fearless Collective, which is completely collaborative, community owned and completely open sourced. I am balancing both those works and both are currently my favorite.

Beloved

Your initiative, the Fearless Collective, consists of a group of artists that create public art as a dialogue about gender and sexuality in India. How did you come up with this idea? What particular issues about women are you most passionate about? Walk us through a workshop and how your engage the community for a common cause?

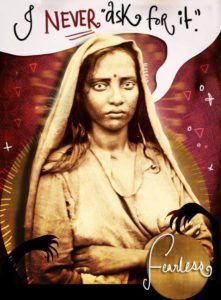

I was in Delhi at a friend’s wedding, after Nirbhaya broke out. And, it was like this kind of instinctive reaction where all of us felt like we needed to go out on to the streets, wearing all our wedding clothes and it was really, really inspiring. But some of it was also quite disturbing, to be honest. Lot of the rhetoric about ‘Stop violence against women’, or ‘Hang the rapists’ or the way the media was fear mongering constantly. It was constantly like you can’t go out at night, you can’t do this, don’t wear what you’re wearing. And that kind of fear spread not only in the media but also to people who I really cared about and people who really cared about me. So fear sometimes comes from a good place. A lot of my friends and people who care about me would say, “Shilo, why do you attract so much attention to yourself?”, “Why are you going out of my house?”, “Why don’t you just stay back at my house?”. A lot of these boundaries were being created as a way of protecting me, but in the process I felt like we were forgetting about the larger picture. The larger picture is that a) fear is always counter-productive to change, and b) no matter what, it’s never my fault. I can’t contain my own life in order to stop this from happening. We don’t need more women being dropped home by their brothers, or husbands, or male friends. We need more women out on the streets, together, collectively. So, I created one poster which reaffirmed to me, that no matter what I am wearing, what time it is at night, I never ask for it. Then, I put up another poster. Then, I put up an open call for posters, which got really good responses. We had hundreds of posters coming from all over the country, and from all over the world, in fact. And what was really interesting about the posters was two things: One, that each of them is was a positive affirmation of how they were creating change individually, and the second important thing was that each of them told a story.

I Never Ask For It

It was really interesting to see how basically storytelling and positive affirmation became two very important things to the campaign, very early on. In a strange way, that connected to my background as a children’s book illustrator. Like I said, storytelling is a way of empathizing. If I know the story of the bear and the forest, then I feel like I am closer to the bear and the forest.

Another thing that also connected to my background as a children’s book illustrator is that I believed that as a child, personal positive affirmation was the only way that brought a change in my life. Someone telling me that you actually can do this. My mom, for example, constantly positively encouraging me is what made me feel like I could paint, or made me have confidence in things I could do. So basically, drawing from those two ideas of how we learn and how we empathize as children can be really influential. Each poster had a story to tell.

The poster below for example, was designed by this woman called Aruna Chandrashekher who works with Amnesty International. This poster, in particular, speaks about how when we talk about Indian culture, which Indian culture are we talking about? For example lot of the women who are part of the Dongria Kondh tribe, they have tattoos, they drink locally made alcohol, they have sex outside of marriage, they have sometimes poly-amorous relationships, and they have piercings. So when we’re talking about Indian culture, surely we should also be able to include culture that existed for thousands of years.

Poster made by fellow Fearless collaborator, Aruna Chandrasekhar

First, it was an online campaign that became viral. But then we also went offline, so the campaign was an open source campaign as well. People could, and still can download any of those posters to protest. We had a whole series of exhibitions across the country which was really amazing to see. As I realized that these stories are spilling on to the streets, I realized that there’s also this common goal between the street art movement and the feminist movement. The feminist movement is entirely about reclaiming public space, and the Street Art movement is also about reclaiming public space. It’s also saying that my art has the right to be along with all the political advertising, and along with all the cinema posters that we see on the streets.

Another thing that was also really important was that while we’re used to seeing thousands of projected images of women all around us, right from the goddesses, we’re surrounded by titillating cinema posters of actresses, to women on fairness cream advertisements. We just have images of women surrounding us consistently and constantly. And what is interesting about the Fearless campaign is for once we were saying that we’re creators of those images, and we’re going to put our own imagery on the streets. So, realizing that actually the most powerful aspect of the campaign were the public art aspect, the storytelling aspect and then finally, the positive affirmation. Basically, the Fearless Collective’s second phase was entirely about street art.

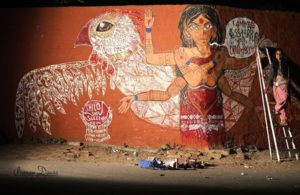

The first wall actually began in Benaras, when I was in a conversation with this sadhu, about how we worship women as goddesses but we rape them in our homes. He said to me back then, “If you want to be treated like a goddess, then why are you waiting for someone to treat you like one?” And I was like, “Yeah. That’s really convenient. Why don’t I just treat myself like a goddess.” But the more I started to think about it, I felt that a lot of times, both in the feminist movement as well as in my own personal life I’ve waited for somebody else. Instead, looking at myself as a catalyst of change was important. So the first image was this huge, huge picture of Durga and her tiger and a little girl and her cat. And the little girl looks at Durga and says, “What we worship, we shall become.”, and Durga affirms “Har Mahila Devi Hain” . Since then, things have really grown.

Fearless Collective Street Art, Varanasi

Then we did one in Chennai about gender and consent in Tamil cinema. So, we worked with larger stereotypes that propagated in a lot of mainstream media about the archetypal, virginal woman in the Indian cinema who always says no until the hero finally prods her enough to say yes. Also, there are so many scenes in Tamil cinema in particular that completely fetishize rape. This whole idea of saving a woman from being raped, and then there are scenes where after he has saved her, he gives her a lecture about how he shouldn’t be wearing this or he shouldn’t be wearing that. There’s so much hero worship in Tamil cinema in particular. So with this one, she’s gently pushing him away and saying, “I am my own hero”. This was in collaboration with the Cinemaholic painter in Chennai, and then this became a part of this larger campaign called ‘I am my own hero’ which was across Chennai.

Fearless Collective Street Art – I Am My Own Hero, Chennai

Then there was one with 40 Muslim girls in this school in Shivajinagar, Bangalore. It was essentially about body image and how we see ourselves, despite being covered in a hijab for most of our live. With each of these interventions, we started to realize that it wasn’t just about painting the wall but painting the wall with the community, and also about the stories being of the community. So we started developing a workshop methodology.

Fearless Collective Street Art, Shivajinagar, Bangalore

There was one “My Home, My Body” in Sion Koliwada, Mumbai, and it was about how the fish in that area are affected by land acquisition. Koliwada, is one of the last remaining villages in Bombay, so there are lots of builders trying to grab that land. Women often have very little access or rights over the land, but yet they’re at the forefront of the resistance movement because they’re most affected by their homes being taken away from them. Very often, our walls, even though gender becomes the entry point, they sometimes work with much larger issues beyond gender as well.

Fearless Collective Street Art, Koliwada

There’s a really interesting story of this goddess called Bahuchara Mata who is the patron goddess of the transgender community in Gujarat. Her story is essentially that she was wandering in the desert one day, and a group of men started to come to her and started to grab at her body. So in a quick movement, she cut off both her breasts and handed them to the men and said, “If this is what you want, then take it.” She ended up bleeding and dying in the desert. The gods were watching all of this and they realized that when she stepped beyond gender, she became truly free. Thus, they made her the goddess of the transgender community, which is really interesting. The affirmation here became: ‘I am more than my body’.

Fearless Collective Street Art, Ahmedabad

Share with us the reaction to this art. What do artists feel when painting on these walls and reclaiming public spaces? How do bystanders react? How has it helped start dialogues?

What’s pretty incredible is that the act of painting the wall is a process in itself. It’s a kind of a ritual of fearlessness. A lot of people we’re with have never painted in their entire lives. So it’s their first time picking up a paint brush. Painting in a public space requires a bravery of sorts, especially for people who’ve never painted before, because it’s permanent. For me, the most magical thing every time is seeing that transition that people make from being very afraid and hesitant to picking up the brush, to joining in and eventually letting the fear disappear. In terms of the impact and reactions, one thing I find magical is realizing that we ourselves can be creators. That to me is beautiful.

Another reaction that’s always really wonderful is that unlike in the rest of the world where painting a wall with a political subject is considered vandalism, in India, it’s somehow almost always considered to be in public service. In the west, when you’re seen painting on the streets, you fear that cops might just catch you. But in India, that’s not the case. We’ve had such wonderful experiences with policemen. At 2am in the morning, they’d switch their jeep lights on so we could have more light to paint. They’d bring us chai. In terms of the reactions of the community, the police and the authorities, it’s always incredibly positive and really supportive. It’s very much like a public service, which is just so wonderful. That is because for me, again, second part of the magic is working within the context, understanding a space by understanding the people there. The process of painting the wall thus becomes into a much larger dialogue about the community itself, about the issues that we’re painting.

Sometimes, however, we do have fights. For example, when we were in Delhi, we were painting with a group of girls from Naaz Foundation in Okhla. It was a very scary part of Delhi, with very grotesque issues. Some of the men there were very upset that there were girls painting their opinion on the streets. That became into a proper fight where we were very angry and they wanted us to stop. That was a rare occasion though.

Generally, we have a lot of support. The whole point is that by creating something in public space, you’re allowing for a dialogue to occur. Then the dialogue continues for many months after we leave. People, as they pass by, keep talking about the wall, thinking about it. That’s the reaction of people.

Have you been able to measure the impact of your art?

We haven’t actually done anything official with anyone measuring the impact. But unofficially, for example, on our Okhla wall in Delhi, we worked with Safecity, where the impact has been pretty interesting because the street that was really unsafe for girls to walk on has become a really safe zone for them. There’s been a lot of feedback from the community saying we now feel safe walking on the street. That particular wall was particularly about ‘the unrelentless gaze’ in Delhi. The men there have this ability to keep staring at you.

We also worked with Safecity further to map zones where women have been stared at. Girls from Naaz Foundation were stared at on the road a lot. That particular street was known for students and boys hanging around. That wall became “Buri Nazar Waale, Dil se Dekho, Aankho se Nahi“. We basically painted eyes all over the streets there. Suddenly, people were brought to awareness and they started becoming a little sensitive. So that wall, in particular, has had some impact.

Buri Nazar Waale, Dil Se Dekho, Aankho Se Nahi, Delhi

Violence against women is a big problem in India and many other countries. What do you think is the root cause of this epidemic in India? How has it affected your life personally? Would you like to share any personal stories or encounters with our readers?

I don’t know if it’s just an epidemic in India, it’s actually an epidemic all over the world. We’re basically rewriting thousands of years of oppression across the world. For me also, this has become particularly interesting because we’ve been working in the Indian context and over time we’ve developed our own methodology. We’re working in Lebanon, Nepal and Pakistan too. I am really interested in seeing how the same methodology can step outside the Indian context and become universal.

Secondly, even though we’re currently focused on gender as an entry point, it’s not the prime focus. With the Fearless campaign, we’re now looking at fear in general. I am very interested in working with other sorts of issues using gender as an entry point. For example, it could be women telling us about land acquisition in coal mining affected areas, or working with women who are prisoners of war in Lebanon. That’s the kind of space that I am also really interested in getting in, using gender as a portal into a much larger issue. We also want to look at fear as something that isn’t just related to gender issues in the country. Having said that, I think picking out reasons and making generalizations about why there’s violence against women is really a complex process. Where do I start? Is it about Cinema, about the kind of ads we see? Do I talk about how women are treated in their families, and how boys are brought up differently? It’s just so complicated.

Do we talk about courtship and dating dynamics in India and how obscure that is? There’s no one thing that I can pick out. But one thing that’s very interesting for me as an artist is thinking about images of women on the street. Basically what the Fearless Collective also does is to try and create images of women on the streets that are community sourced, are authentic, shared experiences, and not projected images of models, or item numbers, or virginal goddesses. I am really interested in seeing the different archetypes of women in the streets, and replacing those projected images. We want to reclaim these public spaces and tell our own stories, and create our own images.

That’s what the original Fearless campaign with the posters did. There were suddenly 400 posters all over the street, along with the goddesses and all of the fair and lovely ads.

Posters for the Fearless Campaign at One Billion Rising in Delhi

What is your idea of an empowered woman?

I think more interesting than answering what an empowered woman looks like, would be to look at what an empowered person looks like.

The last workshop that I did in Chennai, yesterday, was with a group of girls at Stella Maris College. It was about how fear is basically anticipation. So it’s never really about dealing with the reality of what the current situation is, but about, ‘What if this happens to me?’ ‘What if I open the door and someone rapes me?’

So essentially, I feel that fear and anticipation keep us dis-empowered. For me, someone who is empowered is trusting in themselves, and also in the world around them. Another source of power is empathy. That’s why with Fearless we’re really interested in looking at storytelling as a platform for empathy, because as we start sharing our stories with each other, we start caring a bit more. For example, I always begin the Fearless workshops by telling everyone there that my mother was a single mother who brought us up in Bangalore. Our father was an alcoholic who was very abusive, physically. By telling people that right at the beginning, it disarms me a little. People almost care a little more and if you would tell me things that happened to you growing up, or right now, I would care a little bit more.

So I think people who are empathetic are empowered. A lot of ideas like courageous, fearless, and being very strong aren’t just the things that empower us. Empathy, vulnerability and trust are really important. Another very empowering thing is having the ability to forgive. It is something we don’t talk about enough in activism spaces. But in order to transcend and essentially heal, we also have to learn to forgive. With Fearless, we’re really focusing on those aspects of empowerment as well.

Sayfty’s mission is to Educate, Equip and Empower women so that they can protect themselves against violence. What is your message for our readers related to women’s personal safety and the issue of violence against women?

Like I told you, the workshop I did yesterday in Chennai was about how so much fear is anticipation. It’s important that we continue to do the things that we really feel we want to do without anyone stopping us. I feel that more often than not, we’re protected. More often than not, things work out okay. So, trusting that we need to keep doing things we need to do anyway, like trusting to get on that bus, walking out at night, travelling the world alone, if that’s what you really want to do, and not stopping yourself, is the only way that things are going to change.

Bio

Shilo Shiv Suleman is a visual artist with a focus on the intersection of magical realism, art for social change and technology. In most recent years, she’s been engaging with biofeedback technology, and the interaction between the body and art. She has created large scale installations that beat with your heart, apps that react to your brainwaves and sculptures that glow with your breath. She has also designed stages for some of the world’s biggest festivals and conferences. She is the founder and director of “The Fearless Collective” that engages with gender issues and art for social change in India.

As an INK fellow, her work became known when her talk made it to TED, and got over a million views in 2012. She was then chosen as one of the three pioneering Indian women at TEDGlobal, and spoken at conferences like WIRED, DLD in London and Munich. More recently, she founded a collective of over 400 artists in India using community art to protest gender violence for which she was featured in a host of documentaries including Rebel Music by MTV. She was also felicitated with the Femina “Woman of Worth award” for her work with art and gender violence and the Futurebooks Digital Innovation award in London.

At INKTalks

In 2014, her collaborations with a neuroscientist on creating art that interacts with your brainwaves and other biofeedback sensors made her recipient of several grants and residencies, including an honorarium grant from Burning Man for the interactive project: Pulse and Bloom. The biofeedback installation brought together artists, architects, entrepreneurs, builders and neurotechnologists. The project was then featured on a host of international media: BBC, Rolling Stone, MSNBC, Tech Crunch, The Guardian, WIRED and more.

Photographs Credit: http://www.shiloshivsuleman.com