Edna Adan Ismail is the director and founder of the Edna Adan Maternity Hospital in Hargeisa, Somaliland and an activist and pioneer in the struggle for the abolition of Female Genital Mutilation (FGM). She was the only woman minister in the Somaliland government until July 2006. In 2007, her name was added to the Medical Mission Hall of Fame of the University of Toledo, USA. In 2012, Edna Adan was featured in the documentary Half the Sky: Turning Oppression into Opportunity for Women Worldwide, that premiered on PBS.

What was it like growing up in British Somaliland, a British protectorate? Education for girls was unheard of. You were the first Somali girl to attend school, the first Somali girl to have acquired a scholarship to study in Britain, Somaliland and Italian Somalia’s first qualified nurse-midwife and the first Somali woman to drive!

Growing up in British Somaliland was very privileged being the daughter of the ‘Father of Health Care in Somaliland’. My mother was also the daughter of the Postmaster General of British Somaliland Protectorate. Both my parents were educated in Aden in British Yemen Colony so there was never a shortage of reading material in our house. There would be dad’s textbooks which I was not allowed to touch or play with but there were women’s magazines passed on by the wife of the Governor who subscribed to several magazines and periodicals and who circulated them among the senior civil servants and their families. The women’s magazines were beautiful and colourful and soon I began to identify the names of my favorites. Mum would also tell me stories from books and magazines she read. When I began to identify the alphabet, it was always exciting to show my father what I had learnt by identifying the alphabets in my parents’ books.

I was sent to neighbouring Djibouti to attend school there since there were no schools for girls in Somaliland. The first school for girls was opened in 1953, where I became one of the two first Somaliland pupil teachers assisting the British school teachers. That is where I also attended my secondary school education and then sat for an examination held annually by the British to select the top students to be awarded scholarships. That is when I succeeded to become the only girl who won the scholarship which took me to London in October 1954, together with another girl from Aden, Yemen.

You credit your father, a well-known doctor – also known as the Father of Healthcare in Somaliland, for sparking your interest in books and studies. How did he inspire you? Is there a childhood memory that sticks out?

I think the biggest impression that my father left on me was that I always admired his sense of dedication. He was very passionate about his work and he loved his patients. He’d put them in front of everything else.

Once when I was 11, and I was holidaying with my family, a very bad drought occurred. The rains failed and many people lost their livestock. Our people are nomads, so when they lose their animals and when their animals die, they become destitute. There were camps for people who had lost everything. So my dad would travel to these camps, outside of the city to check on the health of these people, and whether they were getting food and water.

And each time he’d travel out of the town he would leave notes for me. The notes would read, “During the couple of days that I’ll be gone, please check on this child. Make sure that he/she received his/her medicine regularly. Make sure that the stitches are removed. Make sure that this patient eats on time.” At the age of 11, I didn’t know where the medicines were, what the diseases were, or how to remove stitches, but as the doctor’s daughter, I’d be checking on the people who were responsible to see that my father’s instructions were carried out.

And then, when he’d come back from his travel, he’d come back with a lot of dust and a two or three days old beard. That was the time when I realized my father has grey hair. Because when he gets up in the morning at home, he’s showered and shaved and he comes back from office clean shaved. But when he came back from the camps, he came back with a three days old beard, and he had grey hair. And I thought, “Oh my God! My dad is not young. I need to help him, I need to do whatever I can.”

Whenever we’d be working in the hospital, I’d be hanging around where he was working. And he’d ask me, ‘Can you roll this bandage for me?’, or ‘Can you wash these instruments?’ or ‘Can you hold his hand for me while I bandage it?’. I used to run little errands for him, and I just felt so helpless, not knowing how to help him more, not being able to do more than I was doing. And that’s what made me want to build a hospital one day. I’d want to build a hospital my father would have loved to work in, with the kind of equipment he would have liked to have. And if he would be using a particular instrument, he would say ‘Oh I wish I had a better pair of scissors’ or ‘Oh I wish I had better lights than this’. He would be thinking out loud about what he would wish to have in this very remote district hospital.

These are some of the things I’d like to do, that is to make available for my people. So whoever’s going to be looking after the sick will not have to go through the same frustrations that my father did. So these things left a very lasting impression on me. Whenever I can’t decide and I have a tough decision to make, I always think of how my father would have dealt with this situation. He’d been an invincible role model for me, a kind of a guiding hand. I always want to do as much as he did for my people. He really loved his people, and his people loved him, and I can never ever be a fraction of what he’d been, or what he’s done.

What fueled your passion for maternal health care?

My initial passion was in health care in general and in nursing in particular. It was after I graduated from nursing that I decided to specialize in Midwifery. My passion started the first time I saw a baby being born. That passion was fueled further since I myself was a forceps baby who survived. However, my parents lost the daughter after me when she too was delivered by forceps and then lost a son when the old midwife who delivered my mother dropped the baby and he landed on his head. My mother had decided to deliver at home and Dad was at work when this tragedy happened. I was six years old and remember the grief of my parents from which my mother never fully recovered. The tragedy of losing a healthy baby is what further fuels me to train as many midwives as I can in proper midwifery practice so that no family will ever go through what my parents had gone through following the loss of two babies after childbirth.

Upon return from the UK, I saw so many women being brought to hospital after they had developed problems and complications arising from the lack of proper midwifery care. For instance, right now, I have a woman being treated in my hospital who was brought to us a week ago with a placenta inside her after she had delivered a baby 21 days prior to being brought to us! She was infected and anemic to the point where we were not sure whether she would ever make it. A week later, she is slowly recovering and has a good chance of recovery. If only someone had brought her to us when the placenta had failed to come out after the baby was born. A trained midwife would either have managed the third stage of labour differently or would have referred the woman to a health facility immediately when she realized that the placenta was not coming out.

Tell us a little about your roles at the World Health Organisation (WHO).

I had a long career with WHO. I was first recruited by WHO in 1965, and my first duty station was as a Nurse/Midwife/Educator in Tripoli, Libya. I was part of a team with three midwives and a doctor. We started the training of midwives in Libya in 1965. And for that, we had to build a curriculum, training guidelines, build a criteria for selection of students, talk to parents to let their daughters go to work. In 1965, daughters in Libya were not encouraged to work outside their homes. It was also a very important task to find girls who had gone to school, who could read and write, and who could understand basic sciences and how to calculate, maybe a dosage of a medicine, a dilution. We did about 6 months of very hard, intensive work with the Government of Libya. That was the first job I had.

Edna, only woman government Minister in Somalia

One year after I went there, I was promoted. The other people who were working with me had different levels of qualification. The WHO put me in charge of the reports and administrative responsibilities for that project I felt very honored because I had earned the confidence of WHO and felt that they trusted me for that very responsible job. So that was my first job. Then, two and half years later, my husband was elected the Prime Minister of Somalia. We had responsibilities back home, so we had to come back. 2 years and 8 months later, I came back to Somalia, because at that time Somalia and Somaliland were united.

During that time, I also devoted one or two days a week to the government hospital. I also did a lot of maintenance work. Gave refresher courses to midwives who were working there. I was told this should not be the job of the wife of a Prime Minister. And I asked, if I don’t do it, who will? If someone had been maintaining the hygiene, it wouldn’t have been in the state that it is in. I felt that that was a good way to show the students and the staff that nobody is too high up in the social status to be looking after these things. So if I am the Prime Minister’s wife, and if I say I am coming to work at 7 o’clock, I wear my uniform and I am there at 7 o’clock. And I’ll speak to the patients with respect, and show them kindness. I have to know that everyone had the right to be treated with respect and dignity.

Prime Minister Egal and First Lady Edna being hosted by the President

So if I can do it, I expect you to do it. So I’d try to be a role model, to show them that you cannot be looking after a sick patient if you do not value a person and respect them as a human being. You cannot be just dishing out medicine or putting bandage on a limb without respecting the person this arm it attached to. You’re not looking after an arm, you’re looking after a person who has a sick wound on their arm. It’s the person that comes first.

Then the revolution happened. In 1976, I went back to the WHO as an advisor on Human Resource Development. They’d keep sending me to Nigeria or to Zambia.

UNICEF also hired me during this time. In July, 1976, I had started a big fight or campaign against FGM. I’d keep going to the UN, the African Union and the Government, when we were launching this campaign. Then, in 1982, I got back with WHO again and started training midwives in Djibouti.

Fighting against Female Genital Mutilation in European Parliament

Later on I came back to WHO; responsible for reproductive health, family planning, general issues, and of course FGM. I travelled to a lot of countries ranging from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, all the Gulf states, North Africa, Morocco to Sudan, Yemen, Somalia, Djibouti. All along the journey I taught a lot, I learnt a lot. In 1997 I retired and went home to Somalia and finished my hospital. It’s been a very, very busy life. And now I have a university on top of the hospital. My people need it , I have the energy and if I can influence and encourage people to help them continue higher education. To give them knowledge, to give them quality care, to make them passionate about what they do, to encourage respect for human life, having an ambition to achieve higher. I want my people to aim for excellence, to compete with themselves and get better each time. We come from a poor country, a developing country, we have nothing. However, I don’t want them to think that we come from a disadvantaged background. Don’t say you have nothing. You have a brain, and that is everything. You should give up saying I cannot do and say, I will try to do.

What was your mission behind starting the Edna Adan University Hospital in Hargeisa, Somaliland? The hospital was built on what used to be a garbage dump. What were some of the challenges you faced and how did you overcome them?

Building a maternity hospital had been my dream since age 11 when I was helping Dad at the hospital while on holiday from school in Djibouti.

I started to build my first hospital in Mogadisho in 1984 before Somaliland separated from Somalia. When the war intensified between Somaliland and Somalia in 1988, family fled Somalia leaving my unfinished hospital in Mogadisho which became taken over by the War Lords. My second hospital here in Somaliland was started after I retired from WHO and I returned to my home country which had no functioning maternity hospital at the time.

The site upon which it was built was the only site that was big enough to hold the hospital I had in mind. The site had been an old burial ground which was turned into a military parade ground by the Communist Regime of Siyad Barre (the Dictator of Somalia). During the war, it became an execution ground. After the war, it became a garbage dumping ground.

A long way to go before completing the hospital construction

When my former husband who was the President of Somaliland offered me this site, I was initially very shocked but then decided that this was where I would build my hospital to turn this site from a killing site to a place of healing. Also, it was in a poor area of town where there had never ever been a hospital in the past. These were the people who needed a hospital because those in the more affluent part of Hargeisa had options that had never been available to the people of ‘Dumbuluq’.

Today, Dumbuluq is my address where I moved into during the construction in the only room that had a door and a shower/toilet facility. I lived there because I had no money left and could not live in rented premises. Also it saved me commuting to work every day. I continued to live there when I was made Minister of Social Affairs and continued to live there when eight months later I was made Foreign Minister of Somaliland. I would receive Delegations here and continue to live here to this day to prove to everyone that if this site is good enough for my patients, it has to be good enough for me as well as to those who wish to associate with me.

First baby born in Edna hospital

Somaliland remains culturally-dictated and male-dictated. Women have no voice regarding their own bodies and women’s reproductive rights are almost nonexistent. You have been an ardent campaigner against female genital mutilation (FGM). You personally suffered the harm at the tender age of seven. What kind of awareness campaigns do you run across the nation that are effective, while still being culturally sensitive? Do you see a shift happening in recent years? Talk about the challenges you face in conveying your message against FGM?

The fact that you and the rest of the world have heard and are talking about FGM is in itself a great progress which would not have been possible decades ago when I started talking about FGM in public. My family, my husband and people all around me were shocked that I would dare speak about such an unspeakable subject.

I approached the topic as a purely health subject as I had always spoken about the need for preventing diseases in children by vaccinating them against childhood diseases; about attending prenatal check-ups; allowing girls to go to school as I had been which is what is helping me now to help patients etc.

Many would come to advise me to stop talking about FGM to tell me how dangerous this could be for me and also politically harmful to my then husband. I continued with respect to our culture and tradition but spoke about bleeding, infections and possible infertility resulting from FGM. These were topics that people could relate to. There is nothing that is culturally harmful to saying let us stop our children from dying of causes they need not die of.

Edna talking to the village midwives in Djibouti about FGM, 1982

Today, FGM is incorporated into the training curriculum of all who study at my hospital and midwives and nurses MUST participate in FGM counseling sessions. Any nurse or midwife who does not wish to fight FGM cannot remain in my training school. That is my ‘pound of flesh’.

We have also completed the second survey on FGM and about to publish it soon. The results of the first survey are available free of charge in our hospital website: www.ednahospital.org

New York Times columnist and bestselling author, Nicholas Kristof, described you as his ‘personal hero’. Who is your hero?

I did not know who Nicholas Kristof was when I first met him. He heard about this hospital because there had been a New York Times report about it, and that’s why he came to visit this hospital when I was building it. He had heard about ‘A Woman of Firsts and Her Latest Feat: A Hospital’ by Ian Fisher. So Nicholas wanted to follow up and know what happened of it. He wanted to know if the building was ever completed, and if it could ever really become a hospital. He wrote to me and asked, ‘Do you mind if I come with a photographer?’ I said ‘Sure!’

Edna with Nichola Kristof, Somaliland

He stayed in the hospital guestroom. He followed me all day. He became my shadow for two days. And I thought to myself that this guy is different from the other reporters I have met. He had his own style and his own way of working. He is so interested in what I am doing. Then one day, I googled him and I realized who he was. I went to him and said I have been spying on you and I just realized who you are. I hope I have not been disrespectful to you. And he said, well I like it that way.

He came back a couple of times after the visit. He also visited for ‘Half the sky’. And then he came again for the documentary, the film. We spent a couple of weeks together, going around collecting footage for our documentary. He has fun and charm associated with him. Just before he left, we had an emergency and he donated his blood. So there is a someone here in Somaliland walking around with his blood. We became good friends. Every year he sends me his tax rebate.

My personal heroes are Dr. Catherine Hamlin who started the Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital and of course, Nelson Mandela.

Describe a typical day in the life of Edna Adan. What do you like to do in your free time?

Which free time ?! When I really need to get the world ‘off my back’, I go for a few hours to our family farm where we have a few camels and stroke the baby ones and get some camel milk from the mothers. I also get a chance to walk in the countryside and get some fresh air both into my lungs and in my brain.

In the old days when I could, I played Golf and also enjoyed power-walking, stamp collection and numismatics. Had some great collections which got lost in the Mogadisho civil war. At present, a foot massage is as good as it gets.

What are some of the day-to-day challenges of running a hospital in Somaliland?

As a non-profit hospital, we charge far less than the public hospitals and far below private hospitals. We also do many surgical operations for free such as inserting a celebral shunt in the heads of children (from all over Somaliland, Somalia, Ethiopia and Djibouti) with Hydrocephalus, do repair of cleft lips and palates, operate spina bifida and club foot.

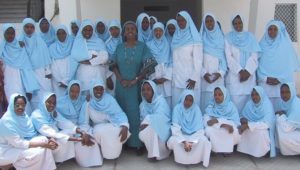

First group of student nurses

The flow of poor patients who have general health problems come to us for help is always painful. Although we never turn a patient away because they have no money, we still need to pay salaries to staff, teachers, buy medicines and pay our bills. The end of the month is always a nightmare because I always have shortfalls which I have to cover somehow even after I contribute my monthly UN pension. There is always a shortage of supplies which even if we had the money we cannot find in our local markets. My biggest worry is what will happen to my hospital after I have gone at which time my pension will also stop.

Surviving triplets born at Edna hospital

You believe in passing on the gift of hope, knowledge, determination and perseverance to the next generation of nurses and midwives in Somaliland. What would be your advice to these young women?

Set your goals, make your targets, work hard to attain them and never give up, no matter who says your goals are difficult or not attainable. You MAKE your goals attainable.

What is your idea of an empowered woman?

A woman who is wise enough to know when to push for something, when to wait for the right moment, and who can wait for that moment financially, emotionally and remains in control of her life. An empowered woman also has the ability to look at options to make choices if alternatives need to be considered.

Sayfty’s mission is to Educate, Equip and Empower women so that they can protect themselves against violence. What is your message for our readers related to women’s personal safety and the issue of violence against women?

Violence against women is a form of cowardice in men. A strong man never violates a woman or a child. Women must never be afraid to say ‘no’ if that is what they wish to say. Do not show weakness because people take advantage of it. Learn to defend yourself physically or verbally.

Bio

Edna Adan Ismail was born in Hargeisa, British Somaliland Protectorate in 1937 and trained as Nurse and Midwife in the UK. In 1961, she returned home becoming the first qualified Nurse/Midwife in Somaliland/Somalia. In 1965, she was appointed WHO Nurse/Midwife educator in Libya but returned home when her husband became Prime Minister of Somalia. In 1986, she was again recruited by WHO to become Regional Nursing and Midwifery Adviser, then Technical Officer responsible for Maternal and Child Health including Gender issues and Harmful Practices such as FGM. In 1991, she became WHO Representative in the Republic of Djibouti where she served until retirement in 1997. In 1998, she studied Health Care in Developing Countries at Boston University.

Upon retirement, she used her pension and personal resources to built and open in 2002 the ‘Edna Adan University Teaching Hospital’ in her home country, Somaliland. The hospital is now a major referral hospital as well as a teaching hospital for nurses, midwives and other health professionals including medical students and Anaesthesia Technicians.

She has received numerous awards amongst which an Honorary Doctoral Degree from Clark University in Massachusetts, USA, (2002), Honorary Fellow of Cardiff University School of Nursing (2008), she was Knighted by President Sarkozy who made her ‘Chevalier dans l’ordre Nationale de la Legion d’Honneur’ of France 2010. In 2010, she was awarded the President’s Gold Medal for her work on Human Rights from the University of Pretoria, South Africa. In 2013, she received an Honorary Doctor of Medical Science from Ahfad University for Women, Sudan. In May 2014, she received an Honorary Doctor of Science Degree from University of Pennsylvania and also became the First recipient of the Renfield Award for Global Health from the University of Pennsylvania.

In 2002, she became the first and only woman Minister in the Government of Somaliland when she served as Minister of Social Affairs, and between 2003 and 2006, she was Somaliland’s Foreign Minister.

In 2007, her name was added to the Medical Mission Hall of Fame of the University of Toledo, USA. In December 2013, she was named among the 100 most Influential people in Africa.

In 2012 she opened the Edna Adan University which trains Nurses, Midwives, Laboratory Technicians, Pharmacists, Anesthesia technicians, Dental Technicians, and Public Health students.

In order to reduce the high maternal mortality rate of the women in her country, her lifetime goal is to train 1000 Midwives to work in remote areas in Somaliland and encourages other countries in Africa to train 1 million Midwives to work in African countries with similar harsh conditions for women like Somaliland.

She serves on many national and international commissions among which :

Honorary Patron, Anglo-Somali Society in the UK

Presidential Commission on Higher Education, Somaliland

Council Member, Hargeisa University, Somaliland

Founder & Chancellor, Edna Adan University, Hargeisa, Somaliland

President of the Association for Victims of Torture

Pioneer in the campaign against Female Genital Mutilation

Spokesperson for education for girls in Somaliland.