The janitor in her school raped a good friend of mine when she was less than 8-years-old. She was in the girls’ toilet, all by herself, when this heinous crime occurred. When she came home and told her parents about the violence, most of which she couldn’t comprehend, her doctor father conducted a finger test to ensure whether or not hymen was still intact. Once he made sure his daughter was not “damaged goods,” he told his wife and daughter that the incident was never to be mentioned to anyone outside of the four walls of their home. He was concerned about the stigma attached to the crime and the repercussions on his social and professional stature. He was also worried that once his daughter, my friend, was a grown-up, there would be trouble finding a suitable boy for her—if anyone found out that she had been violated. That night, along with many other things, a child’s sense of safety and trust in her family was lost. Next morning, my friend’s father sent her back to the same school where her perpetrator roamed free. By doing so, he sent out a message loud and clear: a family’s honor lies in the space between their women’s legs.

Growing up across North Africa and India, I often heard families reinforce one thought: a woman’s body was her jewel that she should always protect. And if even a scratch appeared on it, she was solely responsible for the defiling and degradation. These were no empty suggestions or threats. Guilt and shame are engrained in an Indian woman for inexplicable reasons. Bollywood films have shown us enough examples of sexual assault victims being ostracized and eventually committing suicide. It’s safe to declare that cinema represents life to quite an extent. A survivor, in effect, is raped thrice—first by her perpetrator, then by the society and finally by the judicial system. Questions regarding a victim’s whereabouts, lifestyle, and clothing are asked blatantly. As Naomi Wolf said, “Beauty provokes harassment, the law says, but it looks through men’s eyes when deciding what provokes it.” We seem to be working with the ignorant notion that a woman’s forehead has a tattoo that reads: “Rape me.”

It was the ’90s. I was at a party in my college town of Pune, India when a group of us heard about a couple who had been attacked by some goons, a few days ago, not too far from the venue where we were having a great time dancing to some wicked music. The girl was gang-raped and the guy beaten to a pulp. Rumor had it that the boyfriend was the one who wanted to get away from the humdrum of the city so the couple could get some “alone time.” But once the girl was brutally raped and fought for her breath in the hospital that week, he walked out on her because he considered her tainted. Even though I pretended to smile and have a good time that evening with my friends, my mind was elsewhere. I couldn’t get past the ordeal the woman was dealing with. And to think, Pune was considered one of the safest cities in India and a paradise for college students in those days.

After the party, as a bunch of my girlfriends and I headed back to our hostel, all the guys in our group decided to chaperone us. Not just that, they asked us to wear scarves and cover our faces—only our eyes could be seen. They forbid us from taking the public transport. We were the lean, mean bikers traversing through Pune nights—the girls riding pillion while the boys drove. At 19, I might have been angry about being mollycoddled and given instructions by boys about safety, but I am so glad for their support even today. These men are some of my best friends till date and there is a reason. They understood the mentality of some of the jerks—part of their gender—and protected us from them.

Despite my gratitude, I never could let go of the fact that often a woman could feel safe only when accompanied by a man in most cities in India. As a teenager I wanted to experience the world through my eyes, not through someone else’s lenses. My girlfriends and I were fiercely independent. We would go up to Mumbai from Pune and then take the midnight bus back to Pune. We never informed any of our guy friends about our expeditions because we didn’t want bodyguards. Maybe this was our way of exploring our independence in so-called free India. We would keep to ourselves and never hang out with the wrong crowd or do anything, which was considered inappropriate by Indian standards. Definitely didn’t call any attention to our own selves on the midnight bus journey. But as my brother would say even in those days,”You guys are lucky. Don’t push it.”

See, I was immature then. I couldn’t understand why my brother thought a public transport could be unsafe for a group of girls traveling alone. But the gang-rape incident in New Delhi occurred inside public transport at a little after 9pm. Six men raped a paramedical student, 23-year-old Nirbhaya, in a moving bus on December 16, 2012. The assailants assaulted both Nirbhaya and her male friend with an iron rod when the duo resisted. And after they were finished, the criminals dumped the two of them by the roadside. Nirbhaya passed away in a hospital in Singapore.

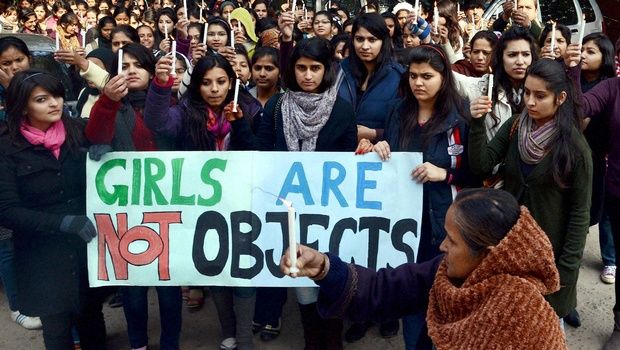

The New Delhi gang rape has shaken up India. Protestors are rightfully demanding justice and asking for safety. Many are seeking death penalty for these criminals. I am glad the Indian government has for once pretended to care. Not too long ago, Jitender Chhatar, a khap panchayat (town council) leader shared his insipid opinion about rape, “To my understanding, consumption of fast food contributes to such incidents.” He further added, “Chowmein leads to hormonal imbalance evoking an urge to indulge in such acts.” India Today reports that Chatar also blames burgers and pizzas for the rise in rapes. Right. First it was the woman’s fault and now it is the food that people eat. Basically, misogyny meets xenophobia openly, and the perpetrators walk away free.

But that’s not the only point of discussion here, is it? The deeper issue is why some men, not all, feel the need to control women physically and so violently. Nirbhaya was gang-raped for hours, mercilessly. Are these weaklings intimidated by women’s empowerment? Do they view women as objects that should be owned? My other question: can we solely keep calling men criminals and let womenfolk walk away without any onus? Every victim and perpetrator is someone’s child. The wrong teachings and learnings begin at home. One of my dear friends, a psychology teacher in a leading New Delhi school, confessed that many young boys even today hold the belief that if a woman is clad in a skimpy skirt, she is “asking” for it.

Rapes will not decline unless we teach our children, at home and school, that women aren’t commodities. Just because we take fancy to people, doesn’t mean they become our property. What is being done about actual incidence of marital rape in India where a man gains sexual autonomy and physically controls his wife night after night for decades?

While I was doing my masters in Pune, a guy (to keep the hatchets of the past buried, I’ll avoid names) told me that I brought out the “sexual deviant” inside of him. And that if I didn’t move out of the place that I was renting along with my best friend from college, he wouldn’t be responsible for his actions—if he violated me. He was the son of an extremely influential man. I remember being in tears the first time he said those words and not being able to breathe. And I am one of the tougher women. I had barely ever said a hello to this man and wondered what made him consider me in such awful light where he thought he could physically own me. At that time, I was also a couple of weeks away from finishing my final exams. I told no one in the family, just a few close friends, about the threat that was looming over me— I was young and petrified and assumed so many things. The girls and guys from my undergrad days would take turns to sit with me on my terrace all night for those weeks as I studied or went to the university. I was scared to be alone, and my friends refused to let me be by myself for even a minute. Ironically, I was worried that if something happened to me, somehow I would be held responsible for the crime. At 21, I didn’t have my personal voice or confidence to comprehend that this man’s lewd intention was a reflection on his perverse mentality. Well, my masters got over, I topped my university, and I left the city unharmed—thanks to my strategic and supportive group of friends. But not everyone is that lucky. Case and point: the gang-rape incident in New Delhi two years ago.

We need to have zero tolerance for violence against women. Society will eventually cease if women aren’t respected and offered an equal place. Attitudes have to change on many levels. I was deeply disturbed to read what the government officials, protectors of law in New Delhi, think. According to an article in the First Post from over a year ago, “The idea that rape is often just a woman crying foul after a night of consensual sex seems to be deeply ingrained in the psyche of Indian police all across the country.”

The burden of rape prevention shouldn’t be on the victims. The government should consider getting troubled men with deranged ideologies serious help. The media along with political leaders and safety keepers of the nation need to stop perpetuating the rape culture. Dismissing rape cases or making ludicrous remarks, just because their daughters, sisters, and wives aren’t victims, isn’t becoming. President Pranab Mukherjee’s son Abhijit Mukherjee made sexist comments and belittled Delhi gang-rape victim’s supporters. Yeah, that’s how much respect an Indian woman is bestowed upon! His apologies or resignation is not what we wanted. To think he could take liberties and utter such insensitive remarks goes to show us the dirty psyche of many Indian males. And that has got to stop!

About the Author

Sweta Srivastava Vikram, featured by Asian Fusion as “One of the most influential Asians of our time,” is an award-winning writer, Amazon bestselling author, novelist, poet, essayist, columnist, educator, and marketing consultant. Born in India, Sweta spent her formative years between India, North Africa, and the United States. She is the author of five chapbooks of poetry, two collaborative collections of poetry, a novel, and a nonfiction book. She also has two upcoming book-length collections of poetry in 2015. Her work has also appeared in several anthologies, literary journals, and online publications across nine countries in three continents. Sweta has won three Pushcart Prize nominations, Queens Council on the Arts Grant for BYOB Program, an International Poetry Award, Best of the Net Nomination, Nomination for Asian American Members’ Choice Awards & Independent Literary Awards, and writing fellowships. A graduate of Columbia University, she lives in New York City with her husband and teaches creative writing across the globe & gives talks on gender studies. You can follow her on Twitter or Facebook

*This essay previously appeared in Halabol India.