“One should not take personal safety for granted no matter where you are. One of the things I always share with young girls is – be aware of your surroundings. How you carry yourself matters.”

You were one of the first women on a FBI SWAT team. Why did you chose FBI and how did you break the glass ceiling?

Looking back, all the signs were there for me going into that career, but I didn’t recognize them. Reading mystery and crime fiction was my favorite things to do as a kid. At 11 I visited Washington D.C. with my family. We went to FBI headquarters (which at that point was still in the Department of Justice). I was very fortunate to have a mom and dad who always encouraged me to do anything. My father always said to me “Be the boss and be in charge of what you do.” I had very supportive parents and they never treated me any different from my two brothers. We took this tour at the FBI headquarters and I raised my hand and asked the tour guide, “Can girls be FBI agents?” and he said to me, “No”. I then said, “Why not?” and he told me because girls would spend all their time painting their nails. I thought, “Well that’s pretty weird.”

Fast forward, I went to college to study pre-med. I wanted to be a doctor so I was still looking at something that was not common place for girls in the 1970s. It was my first failure in life because I had good grades but I wasn’t able to sustain. I was killing myself trying to keep up. Having to realize that I couldn’t be a doctor and figure out what I was going to be was my first big fork in the road for me. I switched majors and still wasn’t sure what I wanted to do. After graduating, I began a job in New York and began exploring further what I want to do. Law school looked interesting so I took the LSATs. I focused in the service area; working for my country, the possibility of having an impact not just here but globally and to be in an environment that was constantly changing and always challenging. Those were some of the core things about who I was as a person. From childhood up they were there with me in that important time.

I looked at the state department, the FBI and the CIA. But back then, you’re talking the late 1970s early 80s, there was no internet. It was about who you knew and it was not an easy thing to do. I literally called the CIA and said that I wanted to talk to someone and they hung up on me. By serendipity they hired a woman at the job that I had. Some of my co-workers knew I was interested in the FBI and they said, “Hey they just hired a new admin assistant and she came from the FBI.” I ran down the hallway in that office to find her. She introduced me to a woman agent and they were, at that point, really focusing on diversification of the workforce in the FBI. So it was perfect timing. I started the process of applying to the FBI in late 1981-early 82 but I did not start working until February 1984.

I loved every minute of it, I came in with ideas when I first thought about coming into the FBI. Behavioural profiling was very new at that time. I knew I could work overseas and to me, everything surrounding national security, espionage, counter intelligence was appealing. I liked the intellectual challenge of working on something that protected our national security but also put me against the best and brightest that other countries had to offer. It also gave me the opportunity to continue my education. I’m exceptionally curious, I never want to stop learning. My roles gave me the opportunity to read and learn about a culture, a society, a country so that I could really understand what I was doing and be more effective at it. That is largely how joining the FBI came about.

What about the physical training aspect? Did you spend a lot of time in the field? Tell us a little bit more about your role.

Lauren at the FBI Academy

The FBI Academy at the time was seventeen weeks long, I believe it is now twenty-two to twenty-three weeks long. It has three segments: academic training, firearms training and physical fitness training. Then there is a practical applications part of it where they create scenarios where you use everything that you’ve done in the rest of it. I was physically active and enjoyed playing sports. I loved that I would have a physical challenge as well. Going through the FBI Academy, that’s what it was. We boxed, we wrestled, we ran and we lifted weights. Everything that you can imagine we did, plus we shoot all different types of weapons. We were learning the law along with it. We were also learning forensics and learning how to lift fingerprints, the importance of latent prints. That physical aspect was intriguing to me. I worked as an agent for many years. The rule of thumb was, for every hour we spent on the street, we had to spend two on paperwork, documenting everything we did. If it doesn’t exist on paper, it didn’t happen.

You led both Counterterrorism and Counterespionage programs in Washington DC. What challenges did you face as a woman and how did you overcome them?

Overall, everyone treated me very well and I experienced very limited amount of discrimination. Most of it was out of ignorance and not intentional. Counterespionage and counterintelligence were one of those areas where there were more women. In that regard, it was fine but there were still very few when I was starting out. I can remember being part of conversations with bosses and they would be talking about me even though I was sitting in the room and I would say, “I’m here! I can hear you!” But again it was just because it was new to them in trying to deal with women in first-time situations. I had a lot of acceptance in the counterespionage area and running that was a fascinating experience. The entity I had when I had it, which was in the mid to late 1990s, is the same component that is now responsible for the investigation of Hillary Clinton’s emails and server. It was also very soon after the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It was fascinating because lots of information was coming our way of people who had been spies for former Soviet bloc countries who were Americans. That triggered another whole series of investigations.

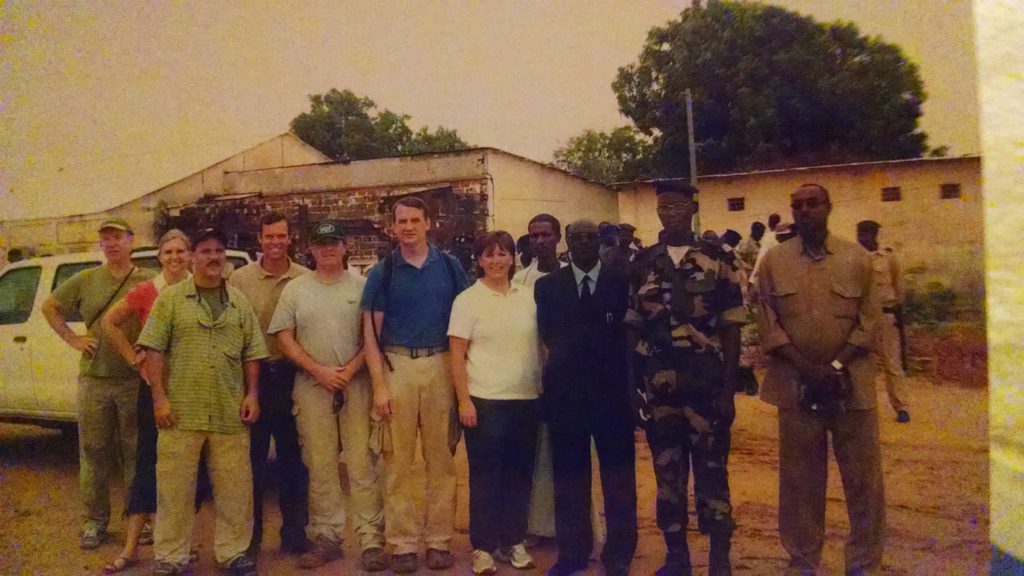

Ndjamena-Chad First Ever FBI Training For National Police

I loved my work in counterterrorism. In the 80s and 90s terrorism was still very bad, which a lot of people forget and the Abul Nidal organization for example, was the most violent out there until Al-Qaeda came along and of course ISIS. So it was fascinating to work on that and also to cover things in the Middle East after the first desert storm war, the first Gulf War. I did run into a couple of challenges there from a couple of guys but by and large the bosses were great. In one situation we had received information that a member of a terrorist organization was willing to talk with us. I had to go to another country in another part of the world to vet the information and see if it was real or if it was all complete fabrication. At that time there were only four women managing nationwide counterterrorism investigations at FBI Headquarters. When this came up and the guys heard that I would be traveling to this particular location and I would be the one making the assessment, several of them expressed their discontent. The man in charge of running all counterterrorism operations, said, “Don’t listen to the noise Lauren. I have total confidence in you. How much money do you think you need to negotiate?” and I gave him a dollar amount and he said “Go!” There was a lot of sniping behind me because at that point no woman had ever done anything like that.

“Women change the game considerably for the better when they are in law enforcement organizations.” How?

Diversity in general in any rule of law institution is important, gender diversity, religious diversity, racial diversity, ethnic diversity, all of it. Because first of all, it helps make better informed decisions. Second, we all deal with conflict in a very different way. For example look at the UN department For Peacekeeping Operations. When there are more women present, several other things become much more positive. There is a much lower likelihood of conflict. Women will go into a situation and do everything they can to not escalate it (I’m not saying that all men escalate. This is a generality). I engaged with people differently compared to my male counterparts. Women are more likely to listen to what everybody has to say and then make a judgment rather than make a judgment on a situation and then sort it out.

In addition, people are much more willing to talk to women whether they are victims or witnesses. I saw that in my workplace when I became a “boss”. (A boss in law enforcement is a term of endearment. When they call you boss, they like you.) Male agents who worked for me would come in an share something personal that was going on and impacting them at work. The first couple of times I thought, “Why are they telling me this? They would never tell this to a guy” Then I realized that was exactly the point. They were sharing very difficult moments of their lives with me because they knew they could trust me and, if needed, I would help them find a solution.

The same goes for dealing with people in other countries, whether they were people we were interviewing or interrogating in Rwanda or a witness I interviewed in Gabon. I negotiated the situation in a way to that made the witness feel more comfortable. In peacekeeping operations there is a lot of statistical information out there that clearly shows that in any kind of conflict and certainly while dealing with sexual violence that happens with men, women and children, the presence of female peacekeepers both civilian and military reduces the chances of that happening again. Conflict comes from a complete lack of diversity. In totality whether it’s tribal, whether it’s gender, whether it’s religious it doesn’t matter, it’s uniform and it’s a complete absence of diversity that helps to create conflict.

Police First Ever Training on Crime Scene Investigation For Rwanda National

The number of women in law enforcement has been stagnant in the US at 12%. In countries like Pakistan, Afghanistan & Iraq it’s only 1%. Why?

I recently did some research myself on this and it’s about 0.9% in Pakistan of women in law enforcement and that’s out of over 425 000 people in law enforcement in Pakistan. India has raised its numbers in the last eight years. They were at about 3.8% and now they are at 6% out of about 1.7 million law enforcement officers. India and Pakistan happen to be in the top 10 countries that are most dangerous for a girl, if you look at the UN Department For Peacekeeping Operations, they do provide gender stats, and if you look at the number of women on the military side and the number of women on the law enforcement side, that percentage is just under 4%. But then if you drill down further and look at the top five countries who contribute to peacekeeping troops to UN missions around the world, India and Pakistan are number two and number three. So you have two of the places where it’s most dangerous to be a girl providing the highest numbers of peacekeeping going into the conflict situations in the world, again with the lowest percentages of women as part of the operation. Women are assigned administrative duties. They are not out there! When they are out there they make a difference.

There are a couple of reasons as to why the numbers are so low. For example, the Scandinavian countries have much higher percentages, they are in the 20s. There are clearly cultural differences but if we step aside from the cultural differences; number one, women worldwide are doing more at home including caring for children. That can be a challenge if you are working irregular hours or if you are in situations that can take you away from home. Even in this country, I am surprised in this day and age, to talk to teenage girls. A few years ago one told me, “I would really like to be on a SWAT team like you, but my mom said girls don’t do that.” I had to suppress the urge to say, “What’s with your mother?” It still happens here. The other thing that happens is, women are pushed into more administrative or perceived less dangerous roles. In the FBI it was white collar crime, because who gets hurt in white collar crime? These are poor stereotypical judgments but that’s what happens. It’s more pronounced in smaller police departments and sheriff’s offices. It influences women because if you know you are only going to get to a certain point and keep getting stopped and stopped and stopped, then you quit and don’t go at all. This is a reason why a lot of women don’t go into law enforcement and why they get out.

What can organizations like the FBI and the UN, do to change the gender ratios? What is your advice on how to balance the gender inequality?

There are a couple of things. First, it takes political will and a lot of people talk about their commitment to it but not as many follow through on that. During his tenure at the United Nations, Ban Ki-moon was very vocal about what he wanted to see overall for women and within the department of peacekeeping operations. He made a lot of efforts to change a lot of things. But he can’t do it alone, any more than a president or the governor of a state can.

I recently did an interview for a journalist in Texas. The chief of police in Texas is frustrated because he has been trying to change how they engage with the community and he has been getting tremendous pushback. You have to get buy in, you can’t compel change. I don’t care what the industry is! You realize, a woman might not have to kick open a door. She may find a way for someone to open it and completely eliminate the need for force. So political will absolutely has to be there.

Second is recruitment. We need to make better effort on recruitment and some agencies do a very good job with that. Then being clear about what the expectations are and then treating people fairly. Again, it is a diversity issue, not just a gender issue. Your looks shouldn’t matter. It’s how you do the job that makes a difference.

What is lacking right now internationally, is the political will. There are cultural issues, not really much in the States but certainly when you look at Southeast Asia, Africa and big swaths of the Middle East. Some are making steps but they’re not enough steps. The level of violence and conflict is dramatically lower in countries that have made these changes. The number of civilian complaints against law enforcement for excessive use of force or abusive power is far lower.

You are committed to investing in women leaders and youth around the world. Tell us about your recent work.

It’s pretty much routine for people, particularly executives of the FBI to say, “Okay I’m at the end of my career. Now I’m going to find this big corporate job for corporate security and make a lot of money, and that’s what I’m going to do” and that’s really what people do. You really need to think through that transition because we’re living longer and healthier lives and after the mandatory retirement in the FBI there is so much more that you can do.

I do a variety of things now including geopolitical and social justice consulting. I work with nonprofit organizations and help them look at reports or studies that they’re doing. Recently I helped co-produce the first ever conference for, with and by the immigrant women of the State of Maine, which is a very diverse population. It was a wonderful way to get to know more people in the community. To see the extraordinary talent that’s coming from other countries and coming here because they’re fleeing conflict. It has also provided me the ability to be a voice for them. I see the talent that’s out there and it’s disturbing to see it pushed over to the side and not taken seriously.

With Vital Voices Entrepreneur-Dalia Saafan

Overall, I would say, focusing on the prevention of conflict and addressing economic disparities is what’s the most important to me right now. Through Vital Voices Global Ambassadors Program, I am mentoring a Somalian OBGYN, a Filipino business woman and an Egyptian entrepreneur. One of my other big passion projects is this new documentary film, “The Uncondemned”. It’s about the first time rape is prosecuted as a war crime by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda. What’s important in all this is that am collaborating with women who have been victims, but more importantly are thriving survivors. Multiple institutions, like the United Nations, Physicians for Human Rights, Panzi Foundation, and Vital Voices are addressing components of the issue of sexual violence. I would like to see how we can leverage all of the different organizations out there, in all spaces, to find the best ways to bring these voices together so that it becomes a part of how we transform our world.

The Uncondemned Panel At Eileen Fisher, Soho

Sayfty’s mission is to Educate, Equip and Empower women so that they can protect themselves against violence. What’s your message to our readers related to women’s personal safety and the issue of violence against women?

One should not take personal safety for granted no matter where you are. One of the things I always share with young girls is – be aware of your surroundings. How you carry yourself matters. Carry yourself with confidence because if you’re fearful, people who commit violent crimes will know it.

It’s knowing that the minute you walk out that door, you are potentially vulnerable. Not that you should live in fear but think about how you want to project in a positive way, not just from a fear standpoint. How you present yourself publicly and how you carry yourself says so much to the world about who you are in every situation. It has a side benefit to safety because if you are doing all those things, people are going to think twice before they come up and do something to you.

The other thing I would say is, trust your gut. When you feel something, listen to it. Listen to it because it’s always right and if nothing happens, so what? When I was in my early twenties, one wintery night, I was walking down a street in New York. I sensed somebody following me. Instead of going home I went into a store somewhere where they knew me by sight. I walked right in like I was intending to go there, not looking around and acting scared. My guts were churning and I was terrified but I walked up to the counter, picked up something as if I was going to buy it and said, “There is somebody following me.” They said, “Okay, we will call the police and in the meantime we will keep talking” and they had cameras in the store. So always trust your gut.

Brief Bio

Following a distinguished career as an FBI Executive, Lauren is now an internationally recognized consultant and geopolitical and social justice expert. She has utilized her expertise in high-risk domestic and international situations, global conflict and terrorist incidents, diplomacy and business throughout the world. She is passionate about, and committed to, working with women leaders and youth around the world to reduce conflict and to address economic disparities. Among current projects, Lauren is advising and collaborating with the producers and filmmakers for The Uncondemned, a newly released documentary film which details the first time that rape was prosecuted as a war crime, in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide. Earlier this year, she co-produced the inaugural Empower the Immigrant Woman conference, for and with, immigrant women in the State of Maine, which also celebrated trailblazers from Iraq, South Sudan, Cape Verde, Cambodia, Burundi, and the DRC, and she helped create and participated in a panel on “Barriers Women Face” for the G(irls) 20 Summit in Istanbul, Turkey, in October 2015.

Lauren’s 29-year FBI career was marked with many “firsts”, including being one of the first women on an FBI SWAT team and the first woman to lead the FBI’s office in Paris, France, where she directed the FBI’s engagement in twenty-four countries, 22 of which were in Francophone Africa. Following her five-year overseas assignment, she directed all International Terrorism investigations of the New York Joint Terrorism Task Force, the largest in the nation, with representation from more than 50 local, state and federal agencies. She oversaw the disruption of many terrorist plots, in the U.S., Africa, and Western Europe and the successful prosecutions of numerous individuals, including neuroscientist and Al Qa’eda facilitator Dr. Aafia Siddiqui, who, in 2014, ISIS sought in exchange for US journalists James Foley and Steven Sotloff. Lauren and her teams have received awards from the Director of National Intelligence, the U.S Attorney General, the Director of the National Security Agency, the Director of the FBI, the Respect for Law Alliance, and the Federal Executive Board, She was the first and, to date, the only FBI recipient of Legal Momentum’s Public Sector Award, dedicated to advancing the rights of women and girls by using the power of the law and creating innovative public policy. Lauren was the first FBI agent selected as an International Women’s Forum Leadership Foundation Fellow and, in 2015, she was honored with Muhlenberg College’s Alumni Achievement Award.

A sought after public speaker and media expert, Lauren provides commentary and insight for Al Jazeera, Alhurra, CCTV America, the Associated Press, The Washington Post, The New York Times, Fox News, Politico Magazine, The Daily Dot, and she is a blogger at the Huffington Post. She serves on the U.S. Comptroller General’s Advisory Board at the Government Accountability Office (GAO), is a Global Ambassador with Vital Voices, a Leadership Ambassador with Take the Lead, a Lecturer at the University of Maryland’s Robert H. Smith School of Business on International Leadership in Law Enforcement, a former Director of the International Women’s Forum New York chapter, and on the Alumni Board at Muhlenberg College. A graduate of Muhlenberg College and the George C. Marshall European Center for Security Studies, she has professional certifications from the Harvard Business School, the University of Cambridge’s Judge Business School, and Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management. You can connect with her via LinkedIn or Twitter

Photograph Credits: Headshot by David Kennerly. All other photographs were provided by the interviewee.