Arunachalam Muruganantham is the founder of Jayaashree Industries. He created, designed, and implemented a system of small-scale sanitary napkin-making machines that improve hygiene and dignity for millions of underprivileged women worldwide.

Mr. Muruganantham is extremely passionate about increasing awareness about menstruation in rural communities, where girls are often forced to drop out of school around puberty. He has earned multiple awards for his work, most notably from TIME Magazine – which named him one of the “100 Most Influential People in the World” in 2014. He also received a National Innovation Foundation award from President Pratibha Patil in 2005.

Tell us a bit about your early life. What was your childhood like? What memory sticks out the most from your growing up years? yourself in one word? What did you want to be when you grew up?

Luckily, I was never born with a silver spoon in my mouth. I was born to a poor hand-loom weaver in a small city called Coimbatore. My father died in a road accident and my mother became the caretaker of the family. No one was a graduate in my family. My parents couldn’t even sign their names. As a result the only available job for my mother was to become a farm worker for a meagre wage of 5 Rupees. With that money she raised my two younger sisters and me in the hope of making me a police officer.

Being a small boy I understood very quickly that it’s only on silver screen that women are heroines. Real life is hard and difficult. I dropped out of school to support my mother. I became a workshop helper and then a welder. I was really happy as a child. I lived a natural life. I knew how to climb trees and run after butterflies. This is missing in the current generation. There is a big gap in the virtual and real world. People nowadays are only sitting in front of screens.

By the age of 16 I was a welder. I used to roam around with the shepherds in my village to understand how a single shepherd boy managed 100 cattle. I learnt everything from nature, by being in nature. I am still learning because I am uneducated. Uneducated people never stop learning. The educated – once they get their degrees they stop learning.

Your were inspired to make a low cost sanitary pad to address your wife’s problem. Tell us how long did it take to come up with your invention? What major challenges did you face along the way, and how did you overcome them? How did the men in your village react in particular?

While I grew up with two younger sisters, I never looked into the problem of menstruation till I got married. We had a small thatched toilet at the back of our house. It had neither a roof nor a door. While growing up I used to see a stained cloth used by my sisters but I never paid too much attention to it. I used to run away seeing it, never asked questions or discussed the same with anyone. In fact, I thought the bleeding was probably because my sisters got hurt while collecting firewood in the forest.

By the age of 24, I owned a small shop and used to make windows and gates. In 1998 I got married to a beautiful girl named Shanthi. It was an arranged marriage and the most important thing for me was to impress my bride. Since we lived in a joint family I never got one-on-one time with her.

To impress my new wife, I used to buy her a 5 Rupees plastic pendant or glass bangles. One day during lunch time, she was trying to hide something from me. I asked her what she was hiding? She said none of your business and ran away. I followed her and saw her carrying a dirty ragged cloth. It had blood on it. It reminded me of the cloth my sisters used. Innocently I asked her if she had hurt herself. She replied it’s that time of the month and every woman goes through it monthly.

Then I understood what it was all about and I asked her why she doesn’t use proper sanitary pads bought from the store. Shanthi replied that the pads were too expensive and if she bought those there would be no money left to buy milk for the family. I was surprised by her answer and realized it was a matter of affordability.

Even today, one of the only places to buy sanitary napkins in India is a medical store. To impress my new wife, I remember I rode my bicycle 13 kilometers one way, to the nearest store to buy a packet of sanitary pads. The shopkeeper asked me what brand I wanted. I didn’t have a clue. Finally he took the packet of pads wrapped it in lots of newspaper and slyly handed it to me like he was smuggling drugs to me. I found his behavior odd and it made me more curious. That curiosity allowed me to go home and open the packet and explore the sanitary napkin with my hands. I touched it, felt it and tried to understand what it’s made of. How many men do that? None! The awareness level about sanitary pads amongst men is less than 1% in India.

It took me 7.5 years to come up with my own affordable sanitary pad. I started designing an experimental pad and gave it to my wife for testing. I had to wait for her monthly cycle to get feedback and when she finally tested it, she said it was the worst napkin that she had ever used and that she was better off with a cloth. I decided to use my sisters as test subjects so that I wouldn’t have to wait endlessly for my wife’s cycles. Eventually, they too stopped co-operating. I looked for female volunteers who could test my pads, but most were too shy to discuss their menstrual issues with me or provide concrete feedback. My wife couldn’t bear my obsession for pads and she misunderstood my interaction with other women and girls and left my home. I distributed my pads to girls in a local medical college, provided they returned them to me after use. When my mother saw me storing a bunch of used sanitary napkins in our house, she was convinced that her son was under a black magic spell. It was very difficult to get women to try my product and so I decided to test the pads on myself. I used to wear the pads and using a football bladder with animal blood test their effectiveness. When my fellow village men saw me washing my blood-stained undergarments, they concluded I’m suffering from a sexual disease. I became a subject of ridicule in my village. As menstruation is a taboo subject in India, I was ostracized by my family and the villagers. One night I fled the village.

You have devised a simple and low-cost sanitary pad making machine that could be operated with minimal training. How did you pitch your machine to rural women across India? What were their initial reactions and how hard was it for them to adopt something like this?

In India the only place to evolve this idea was at the Indian Institutes of Technology (IIT). I sold everything to go to Coimbatore. I used to donate my blood in a government hospital for money. I stayed in a room with 5 other people for 5 years. I sent my machine to IIT. They criticized the simplicity of my machine. Corporations purposely make machines complicated so that they can make profit. I however, still make my machine on wood and kept it simple. This is an equipment for creating livelihood for women especially mothers.

Scientists at IIT criticized my machine and questioned how it would do against American machines? While I understood their criticism, I couldn’t respond due to my language restrictions. I took my first machine to Madhubani, Bihar (near the India-Nepal border).

I run a company called Jayaashree Industries without any marketing. I work in villages. I make money not through the sale of my machines but through my lectures abroad.

In rural India, a large percentage of people depend on agriculture for their livelihood. When crops fails farmers commit suicide. That is why we wanted to offer this as a non-farming sector livelihood for rural women. Only about 10-12% of women in India use sanitary napkins. We give our machines to rural women, it act as an intermediary and helps them in getting loans from banks and not-for-profit organisations. These women make affordable sanitary pads, sell them to other women in the village, as well as spread awareness and impart hygiene education.

As sanitary napkins are being used in more and more Indian households, waste managers and urban local bodies are staring at growing mountains of non-biodegradable waste that are littering our landscape, clogging drains and fast eating into already-scarce landfill space. Can you talk a bit about managing menstrual waste? Are your pads biodegradable?

My pads are bio-degradable. Detailing is used to educate women about the process of how to manage waste. We provide in-depth training and menstruation education.

What are some of the myths in India associated with menstruation? Why do sellers wrap sanitary pads in brown paper bags or why do parents not openly discuss this topic with their girls? What can men do to support women during their periods, and this natural phenomenon?

Menstruation is a social taboo. Raising awareness is key to engaging men. Initially retailing was the way to go, then e-tailing became popular. My model is Detailing. You need to spend time, spread awareness and make the topic of menstruation viral. We have created 890 brands of sanitary napkins in rural India! It’s a sustainable livelihood. We are creating livelihood for women and helping girls get education and go to school. I want girls to go to school and solve a social problem.

Parents are teaching their children to look for opportunities, not to look for problems. We use a women to women model. Women can go to any other women and ask questions related to menstruation. There are lots of social taboos in India. For example: In Uttar Pradesh, it is believed that if unmarried girls use sanitary pads and if dogs get access to those used pads, the girl will not get married or a family member will die.

A tribal community in Tamil Nadu believes that if tribal women use sanitary towels, the goddess takes away their vision. To break this myth, women made and used sanitary pads for three months to show others that nothing happened to their eyesight.

The Indian government has subsidized sanitary pads. Have you received any assistance from them? Does this step or do the big multinational sanitary pad companies pose a threat to your initiative?

There is no awareness and any subsidies by the Indian government is a marketing gimmick. They are dropping sanitary pads from a helicopter. Nothing is happening.

MNCs often call me. The first call I received was from Unilever in London in 2011. They said, “You succeeded in the domain we failed”. They asked me are you ready to share the secret with us? I’ve spoken at Google, Microsoft, IBM, Intel and other companies. In my honest opinion unless the company is connected to a measurable social impact, it will vanish in thin air.

Who do you admire the most and why?

I am totally self created. I don’t have a role model. Every human being should be original. I don’t look up to anybody for inspiration. Luckily I never followed anyone else.

What is your idea of an empowered person?

An empowering person is a leader. The moment you are empowering somebody you are a leader.

Sayfty’s mission is to Educate, Equip and Empower women so that they can protect themselves against violence. What is your message for our readers related to women’s personal safety, and the issue of violence against women?

Give a sanitary pad to each and every Indian girl, it will change the GDP of the country. If you keep 50% of the population of a country in the kitchen it will never progress. Developed nations are those where women are empowered. Women empowerment should happen at the girl’s level. Give proper primary education which is the key to the success of the country.

Don’t use your education just to survive. Use your education for solving a problem in the society.

Bio

Arunachalam Muruganantham, a social entrepreneur, has given women from low income groups in India dignity, by making it possible for them to produce and buy affordable sanitary towels. From a poor background in the South of India, Muruganantham created the world’s first low-cost machine to produce sanitary towels and has innovated grassroots mechanisms for generating awareness about traditional unhygienic practices around menstruation in rural India. According to a report by market research group Nielsen, “Sanitary Protection: Every Woman’s Health Right“, the penetration of sanitary napkins is an abysmal 12% among menstruating women. 88% of women in India are driven to use ashes, newspapers, sand husks and dried leaves during their periods. As a result of these unhygienic practices, more than 70% of women suffer from reproductive tract infections, increasing the risk of contracting associated cancers.

After several years of research and toil, this rural school dropout from Coimbatore district in Tamil Nadu, built his own sanitary pad machine. The National Innovation Foundation in Ahmedabad helped him procure a patent, which he says he never intends to sell to a multinational company or a private investor. “The purpose was not to exploit the patent. I am using the same IPR to empower women in India. I am making them owners of this project, not workers.”

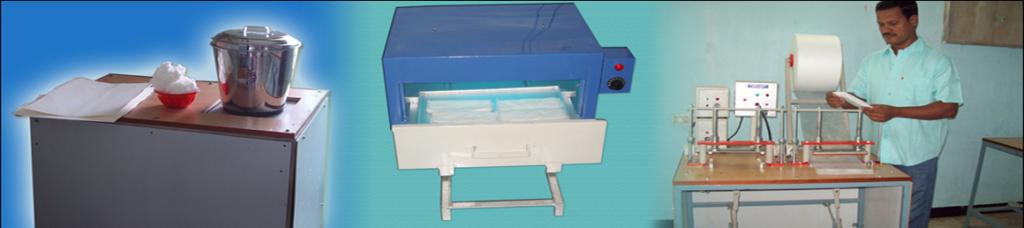

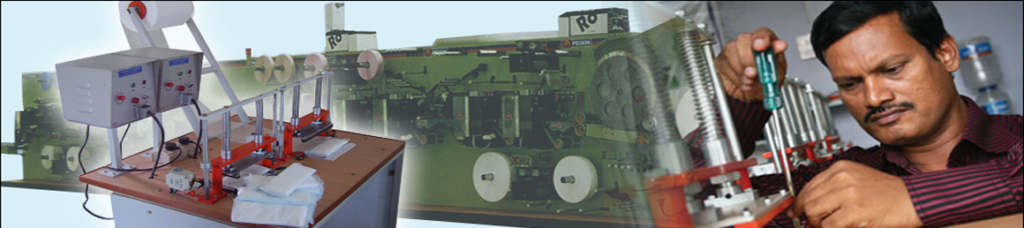

Muruganantham re-engineered a low-cost sanitary pad machine, and in 2006, won the award for the best innovation for the betterment of society from the Indian Institute of Technology – Madras. He also received a National Innovation Foundation award from President Pratibha Patil in 2005. Currently more than 2,000 machines made by his start-up company, Jayaashree Industries, are installed across 26 states in India and 10 other countries. Muruganantham sells his machines directly to rural women through the support of bank loans and not-for-profit organisations. A machine operator can learn the entire towel-making process in three hours and then employ three others to help with processing and distribution.

Vision of Muruganantham: Micro Level Sanitary pad making – livelihood creation for poor women and uplifting women hygiene – more dignity to Women. Muruganantham says, “Making India into 100% sanitary napkin using country, from current level of less than 5% in rural areas. Generate employment for one million women.”

He is currently planning to expand the production of these machines to 106 nations.

In 2014, TIME magazine placed him in its list of 100 Most Influential People in the World.

Master’s in Public Health Degrees Listed Muruganantham as “The 30 Most Influential People in Public Health”.

Menstrual Man is a 2013 documentary film by Amit Virmani. It premiered at the 2013 Full Frame Documentary Film Festival.

TED Speaker: https://www.ted.com/speakers/arunachalam_muruganantham

INK Talks: http://www.inktalks.com/people/arunachalam-muruganantham

TEDxGateway Mumbai, 2012: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u1iWhljEbTE

Note – All images courtesy Jayaashree Industries