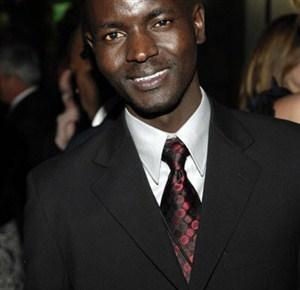

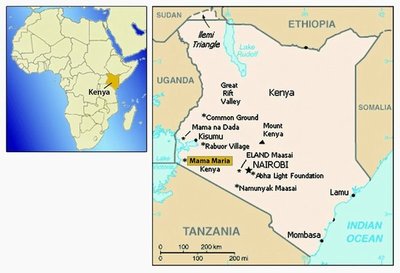

Peter Kithene, is the founder of Mama Maria Clinics – an innovative, sustainable healthcare solution for Kenya’s rural poor. As an orphaned teenager in Kenya, Peter raised three siblings by himself. During his undergraduate years at University of Washington, he raised enough money to found a health clinic in his home village. In 2007 he was named as CNN’s Global Heroes “Medical Marvel” honoree for his work in developing rural healthcare in Africa.

Can you talk to us a little bit about your childhood and how that played a large part in your motivation to start the Mama Mia Clinic?

There are two things that really struck me as a kid growing up; the love of my parents and the loss of my siblings. I was young at the time. I am the second one of my family. My parents had lost their first born and then I came and I survived. The third born, the child who followed me died and then four kids died after that. But there was a lot of love. I was really loved and my parents spent a lot of time with me, loving and encouraging me. As a kid when you see your siblings passing away, you feel helpless, you feel like you can’t do anything. I was naïve growing up and all I kept thinking was, “I wish I could grow up and do something!” So, I grew up and worked hard. I wanted to have a place where kids and parents could go get help when they get sick. My parents, neighbours and many other people were losing their loved ones. The suffering, sadness and pain I saw growing up, really struck me. It was only later in life, I realized that these health related losses are very preventable.

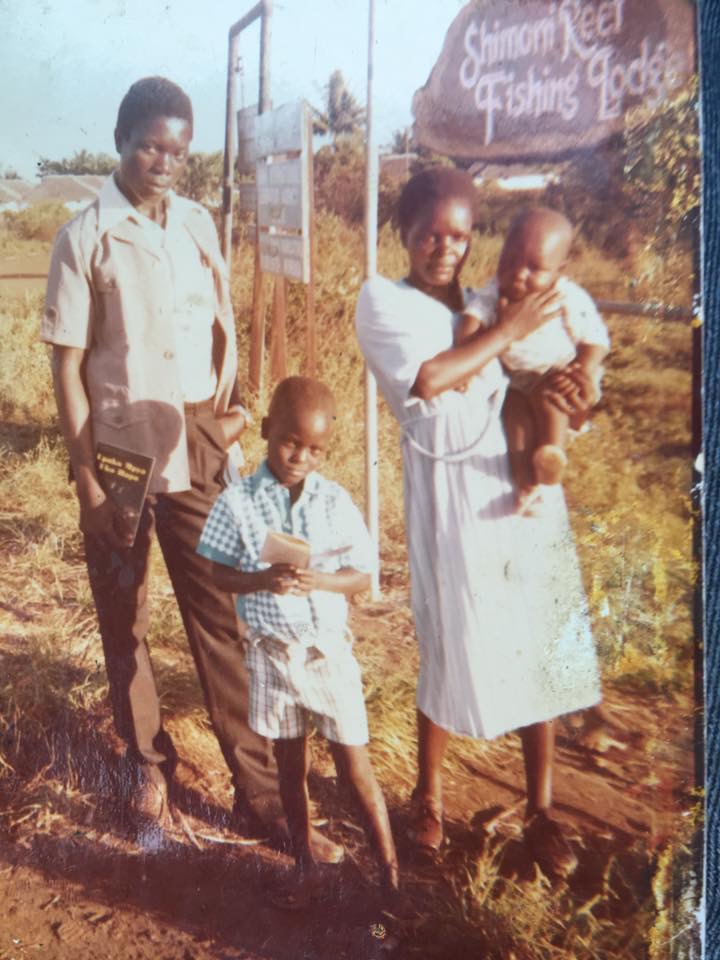

When I was growing up in Africa, things were a little bit different. There was no help (literally). You are doomed if you were born in rural Africa and you are even more doomed if you do not have parents. My parents passed away when I was 12. Luckily now, things have changed. There are a lot of opportunities for children to study, scholarships are available, people use social media to tell their stories and receive a lot of help. I had none of that available to me.

The idea of leaving the village to get an education was laughed at. People would say, “You are crazy. Look at all these kids around here. There is no way you are going to achieve these dreams.” But I had this burning desire inside me and I had strong faith that I was going to get out of the village and get an education. Looking back now, I feel, there is a higher power that protects us, guides us, empowers us, and is beyond our abilities.This power played a strong role when my parents passed away.

I had been a very good student in school. I was always at top of my class and my parents would often tell me that I would do well. The only friend I had, who I was faithful to, was school. I would make sure I go to school every morning. And even after my parents passed away, I made sure to go to school every morning. I had no money. When I was in grade 8, we had to study at night so my classmates and I signed up to do odd jobs for people. We would go weed their farms and they would give us money. But going through that was hard as a kid. At that time, there was just one school in Kenya that provided scholarships to disadvantaged kids. There was only one school in Nairobi and given how things were in Africa, if you were not enrolled or did not have any connections, you didn’t stand a chance. People in my village used to tell me, “Oh you are smart, you can get in there but we are not connected. We don’t know anybody!” But I would reply, “Whatever happens I will go to school. I will apply to this school and I am sure I will get in”. Nairobi is a big city, a ten hour drive from home, but faith kept me going. I am a man of really strong faith and think that something good can always happen.

Was money ever a problem? Was education free or were there barriers to obtain an education?

Education was not free at the time. Primary education was free but again, you had to chip in and put in some money. That is why we would go and work for people. But high school education was never free, it was extremely expensive! Most kids would finish 8th grade and then stay back at home. After my parents passed away, I went to live with my maternal grandma. Some of my uncles would always say, “All of us should just go fishing.” and my family would ask, “Why do you work so hard? You are not going to go anywhere after grade 8.” And it was true, most people didn’t because there was no money to go to high school. But as I said, I had faith that if I worked hard at school and got good grades, I would get into at least one school in Nairobi. And that is what happened. I topped in my district and then I sat for the grade 8 exam and was surprised with a letter from Nairobi. It read, “You have got a free high school education! Come on over! Don’t come with anything, we will pay for everything!”

Education is a really important component in your life. While you did have a history in the realms of health, why didn’t you pick education as an area to work on? Why health?

Without education, a lot of things in my life would not have been possible. I believe that both education and health care go hand in hand. When I was in high school I would go and volunteer in other schools and teach as well. I did not see my oldest brother Kennedy getting sick but I do remember my younger sister Caroline’s (we all had these American names) funeral.

Before his fifth birthday, my brother James, caught meningitis (long before the vaccine existed that could have helped him) and his condition became worse because there was no hospital to take him to. The local dispensary would just give him painkillers without any diagnosis. Nobody knew what was going on until it was very late. We took him about 18 miles from where we lived and we had to be rushed across the border to a big hospital in Tanzania that saved his life. But, by then he had lost his speech and hearing. He couldn’t talk.

Later on, after I came to the U.S., I got some money and sent him to school so that he could finish high school. For the first time in his life, he actually learned sign language and the ability to communicate. But a person with those disabilities, put in that environment, has it very hard. He had very few opportunities.

So, for me I just want to give people the opportunity to live so that they can dream and go to school and do whatever they want to do. But to do all of this, you have to be healthy. You have to be alive. Now, a parent in my community has the comfort of knowing that when his/her child gets sick, they will be treated very quickly and will be able to go back to school. For me it’s about giving life. Eventually maybe I will invest in education too. Right now, my dream is to make sure that people thrive, are healthy to dream, to go to school and do whatever it is that they want to do.

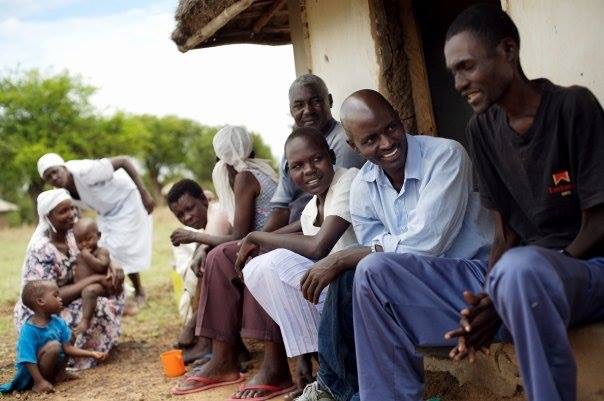

Mama Maria clinic provides health care services and empowers the community by training and giving jobs to widows and disadvantaged people. Did you ever face any opposition because you work with these women? How does the clinic promote gender equality?

When I was growing up, I saw my grandma, my mother and many other people faced with lack of opportunities to earn even $30 a month to feed their family. So when I started the whole idea of creating a safety net for these people, I wanted to make sure that they had access to both food and housing for their families. And this just made me so happy. There was a very subtle opposition around those kind of ideas. We belong in a community where the strongest are rewarded. So I am more respected now because I went to America but I feel, in my hut I am no different from any of those people who weren’t in school. Whenever I go back home, I visit my friends who have AIDS and some of them are struggling and I see myself in them.

People now look at me differently. They say, “You shouldn’t reach out to these people. You should be in our class. You belong to this other of class of people.” They ask “Why are you doing this? I am misunderstood and I struggle with that. That’s the kind of opposition I face, where people haven’t accepted the idea of reaching out to the less fortunate in the community. And the less fortunate in these communities are widows, and really poor people who are working so hard but they don’t have the opportunity to get out of there.

The name Mama Maria is very welcoming. I don’t think I have gone out proclaiming gender equality at the clinic. But the deeds, the name and everything that happens at the clinic is naturally gender friendly. It’s a home for women and anybody can be who they want to be at the clinic. Women naturally take on very tough roles. There are women in charge of many things and I think, “Wow! She has really fought hard”. There is a natural openness and there is an openness to whatever the women feel like. The policy is, if there is a job, that job goes to the less fortunate. The less fortunate happens to be mothers and women. They are very well represented.

To Keep your clinic sustainable you charge a nominal fee for all services. Nothing is provided for free. Why?

A few days ago, I was reading about the government guidelines for charging services in Kenya and one of the things that struck me the most was the fee for childbirth. The fee for child birth according to the government should be 40,000 Kenyan Shillings. That is $400 in a private hospital. If you come to Mama Maria we charge $20. When you compare $20 to $400, it’s nothing. Our agenda is not to make a profit, but we do charge something to keep the clinic going.

There was a case of a woman who had a really complicated birth issue. I drove her 9 miles to a district hospital; more than an hour on a rough road during midnight. When we reached the hospital I was told, “We can’t take you until you go out and buy all these things.” They gave me a list of things that I needed to buy. I was driving with the patient at night till I found a corner stores in town. I bought these things on the list and at the end of the day, everything costs around 3,000 Kenyan Shillings. I brought the patient back and they did the procedure. The reason I am sharing this story is because, when you buy the things they ask you to buy, it costs about 3000 Kenyan shillings. If we had that same delivery at the clinic, we would have charged 200 shillings. So we do charge a fee but it’s just for the survival of the clinic.

I went to the government and told them what I was doing, they throught ours was one of the best models to work with and they reimbursed us for some of the services that we delivered. This was really good because they only work with big hospitals but big hospitals are very expensive and people can’t afford them. So to get that reimbursement has been very helpful.

Do you still play soccer? As an intern at the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, during an event you taught people to make your own soccer ball from recycled material. What does soccer mean to you and what have you learnt from it?

I don’t play a lot of soccer anymore but I do kick soccer balls around. We made hundreds of soccer balls. I think probably 500 soccer balls. And that day in Seattle all these people were just kicking their soccer balls in the streets. It was a very beautiful day.

For us growing up in Africa, that was the only sport we had. We didn’t have to go to the shop and buy a soccer ball to play the game. We would have a really beautiful get together making these soccer balls because of the teamwork. You get strings, you go get some old materials, you get together as kids and we would have fun and bond and then exercise. When you look back as an adult, you think, “Wow! That’s what was going on.” We were just bonding and forgetting a lot of things that were going on in our homes. Because most of us didn’t have food at the end of the day after playing soccer. Or probably, we didn’t have food because we started playing soccer. The joy of having all these kids together, made us forget about everything else. When we were on the soccer field, we forgot if we were orphans, if we were poor. We just liked having fun. When you look back as a grown up now, you truly appreciate those moments. They make sense.

What’s the biggest challenge you face currently? What are you doing to address it?

The biggest challenge is working to pool resources from a community which is poor. There are no financial or human resources and there is no electricity. Everything is really hard and to get all of these things one needs to look outside of these communities, motivate people and drive them to go back to these poor communities. I have done this for ten years and this poor environment is really a big challenge.

There is poverty. People try to steal things from the clinic. There are people who are not motivated to work. Once you train a medical doctor or a clinical officer they don’t want to go and work in poor areas unless you pay them a lot of money. People start by committing for a month or two and once the work becomes really hard they quit. So if you are someone like me, who is really committed, you get frustrated sometimes because you think, “Why is no one else seeing this? Why am I the only one?” People don’t commit and for a while, you are on your own. But I look at it as, we all come into this world with different talents. If you are a dancer, you dance. If you are a soccer player, you play soccer. Not everybody can be these things.

The first thing I do to overcome these challenges is be persistent. I have joy and faithfulness. I do my soul searching and say, “Believe that I am doing the right thing.” Over time, you start meeting people who will commit, but there are very few. I stay very firm on my beliefs and seek out relationships. My relationship with the government of Kenya has been the most rewarding one.

You have two sons. What is the one thing you want to teach them about women’s empowerment and the world they are going to grow up in?

I was reading this idea of spontaneous compassion. I want my boys to be compassionate. They have a mother who truly loves them. I want them to see that love and share that love with the people. They are growing up as black people in America which has its own challenges. I did not grow up as an American but I am someone who has a very strong idea of where I come from and how things are different. So I want them to be aware of issues the less fortunate face in our communities and the weight that the women bear. Be aware of these worlds and respect women and treat them with all the love and care that they deserve.

Sayfty’s mission is to educate, equip and empower women to protect her against violence. What’s your message for our readers related to women’s personal safety and the issue of violence against women?

I think that people who are violent against people, specially women, don’t belong in the community. You belong somewhere else. I think people who abuse women are cowards. I have two little boys and when I read stories about people abusing children, in my head, those children are no different. We should just rid ourselves of people who abuse women. A sex offender registry in Kenya should be in place and people should be ashamed. You hear these stories and you think “wow”.

My message to women is stay strong, be aware of the environment and make sure that you report those incidents without any fear or intimidation. If you see any element of class injustices, you stand up! When you stand up, people will support you. Regardless of disagreements, people will support you because you stand on the ground of truthfulness and justice.

Bio

Kenyan native, Peter Kithene, is the founder of Mama Maria Clinics – an innovative, sustainable healthcare solution for Kenya’s rural poor. Peter Kithene holds a BA in Psychology from the University of Washington. Peter has successfully combined his unique background and visionary perspective on how and why rural villages, like the one he was raised in endure the problems they do – along with his education – to create a sustainable answer to the problem of healthcare. In 2007, Peter was named, out of a pool of more than 7,000 applicants from 93 countries, as CNN’s Global Heroes “Medical Marvel” honoree for his work in developing rural healthcare in Africa. In 2008, he was also called out as one of University of Washington’s “Wondrous 100″ — one of 100 described as UW’s “extraordinary and influential living graduates.”

Images copyright © Peter Kithene