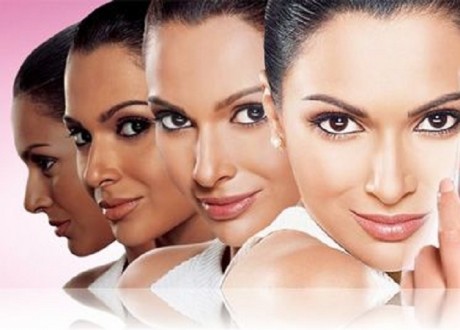

Ever since I was a little girl, I remember the cosmetic industry in India would prey on the insecurities of women—manifested by the society obsession with pale skin—and promote the use of skin-whitening cream. Ayurvedic Vicco Turmeric cream, made with turmeric and sandalwood, was considered the smell of marital bliss for “good” women. Fair & Lovely, another skin lightening cream, promised visibly fairer skin in weeks. The implication: light skin makes you attractive while darker skin does not.

In one of my essays, “Racist or a Victim,” published in an American anthology, Voices of the Asian American and Pacific Islander Experience, I share anecdotes from my childhood about a cousin aunt on my mother’s side, who spent her day rubbing “fairness creams” hoping her skin would become light. She was considered unsuitable bride material by prospective suitors because her complexion was darker than the benchmark they had in mind. Never mind that she was an educated, working woman with a warm personality; random strangers and close family members would pity her and sometimes share tips on “beautification.” Mind you, I am talking about educated, professional, upper middle class stratum of the Indian society.

Her story never left my side, even as I grew older. The impinging sadness in my cousin aunt’s eyes was the first time I became aware of our society’s dirty psyche. I must have been barely nine. With time, I would overhear innumerable stories about families having to pay dowries to get their daughters married. Women tortured by their husbands and in-laws because of their darker skin tone.

If you want to comprehend the level of pressure on Indian women to have paler skin, read the matrimonial columns in the nation’s newspapers. Often taken out by the boy’s family, the advertisements specify that they are seeking “tall,” “fair,” and “convent-educated” women. Sometimes, there is emphasis on “very fair.”

Indian women have been raised to believe that fairness/paleness is beauty. From the time you are a pre-teen or even before, your abilities are judged based on the color of your skin. I have interviewed women who, when pregnant, ate certain foods like saffron so they would produce light-skinned babies.

On one of my last trips to Asia, I noticed this little girl Maya (name changed to respect the privacy of the child) religiously cleanse herself with homemade scrub everyday. When I teased Maya about her daily “beauty-ritual,” she touched my face and said, “I want to look like you when I grow up. Dark skin is dirty.” Let me clarify that I am no beauty pageant material by any stretch of imagination; basically this child is growing up with the same notion that Indian women now have for generations—beauty is what’s on the surface—the lesser the amount of pigmentation on your skin, the prettier you are considered.

The conversation with Maya broke my heart. Me telling her a few times a year that she was beautiful no matter what would not alter her mindset. The damage was long done. What was more disgusting was that Maya’s family and others around expected me to feel flattered because I had a “fan.”

It’s not just the cosmetics industry that reinforces stereotypes about race and gender. I have interacted with people who show favoritism to their “fairer” child. Then there are people from even my generation who assume that women with “fairer skin” (mind you, the “fairness” is all relative here) have no worries and struggles in their lives. Yeah, like that’s what I write on my resume under “skills.” As if lighter skin helps me make friends and land book deals and teach students and gives me the strength to raise my voice against social issues. On seeing my picture on my first book’s back cover, one of my mother’s acquaintances said, “Your daughter is fair. Like a foreigner.” She ignored my hard work, only noticed the color of my skin, and then wanted me to appreciate her?

I have met Indians in the west, who hire cleaners based on their ethnicity and skin color but are quick to victimize themselves as “minority.” These are the people who wear Louis Vuitton, voted for Obama, and send their children to Ivy-Leagues. They hide their hypocrisy under their Hermes accessories.

Just when I thought that the Indian society couldn’t degrade women any further, I was proven wrong. I watched a commercial for an Indian product: hygiene wash called Clean & Dry Intimate Wash. This skin-lightening product promises Indian women “fresher” and “fairer” private parts. The commercial shows a woman clad in trousers, looking melancholic and serving a cup of black coffee to her partner. The partner continues to read his paper and doesn’t notice the woman. The symbolism is that the woman is sad because her nether parts are dark, like the cup of coffee in her hands, and as a result, her partner is disinterested. The commercial makes you believe that the man would much rather look at his black cup of coffee than her darkened female parts. But as soon as the woman goes for a shower and uses the Clean and Dry Intimate Wash, she looks much happier—an animation of a hairless and whitened feminine crotch is shown. Post shower, once the animated female parts are lighter-colored, the woman appears in a pair of shorts. To communicate that she is available and boasts tinted-nether parts, she picks up her partner’s keys, jumps on the sofa, and stuffs his keys inside her shorts. The guys seems attentive to his woman and takes her in his arms.

Has anyone stopped to ask what a woman wants? How does she feel when the society evaluates her abilities and sensibilities based on physical appearances? For a country like India, motherland with such rich culture and heritage, how is it okay that we disrespect women, break them down psychologically? It would seem that it’s not the dark skin, but the Indian psyche that is dirty.

This essay previously appeared in Halabol India.

About the Author

Sweta Srivastava Vikram, featured by Asian Fusion as “One of the most influential Asians of our time,” is an award-winning writer, Amazon bestselling author, novelist, poet, essayist, columnist, educator, and marketing consultant. Born in India, Sweta spent her formative years between India, North Africa, and the United States. She is the author of five chapbooks of poetry, two collaborative collections of poetry, a novel, and a nonfiction book. She also has two upcoming book-length collections of poetry in 2015. Her work has also appeared in several anthologies, literary journals, and online publications across nine countries in three continents. Sweta has won three Pushcart Prize nominations, Queens Council on the Arts Grant for BYOB Program, an International Poetry Award, Best of the Net Nomination, Nomination for Asian American Members’ Choice Awards & Independent Literary Awards, and writing fellowships. A graduate of Columbia University, she lives in New York City with her husband and teaches creative writing across the globe & gives talks on gender studies. You can follow her on Twitter or Facebook